[Order Michael Finch’s new book, A Time to Stand: HERE. Prof. Jason Hill calls it “an aesthetic and political tour de force.”]

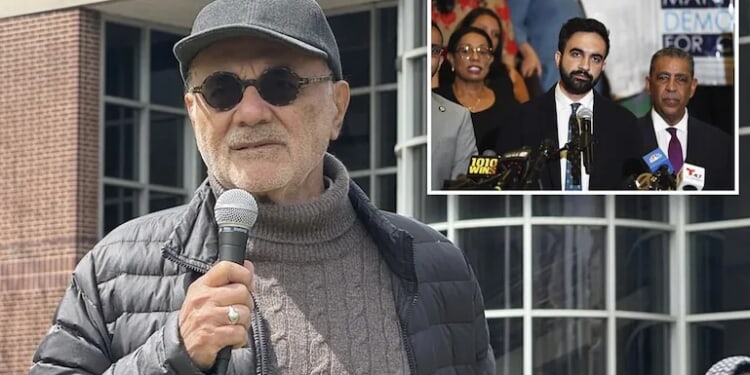

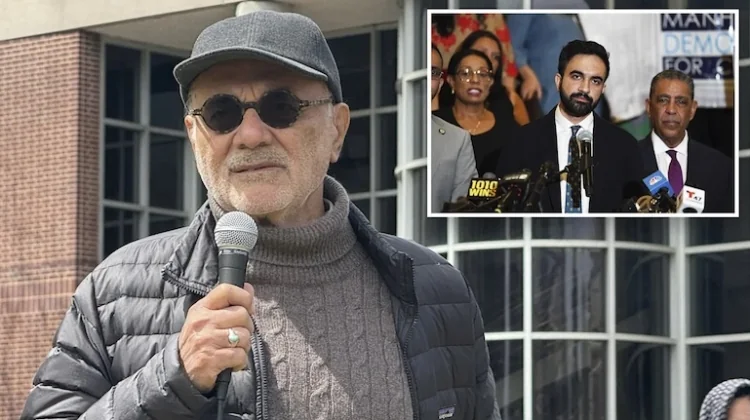

Zohran Mamdani, the almost-certain next mayor of New York, is a Marxist, though he denies the fact. And he learned his Marxism right at home. His father, Mahmood Mamdani, is a Marxist academic, a professor at Columbia University who claims to have become a communist while studying in the United States. The generosity of the U.S. toward a student from the Third World was turned against the giver.

Born in Uganda, Mahmood Mamdani says that in his youth, he had little awareness of political and social issues. He was awakened to political and social activism because of the generosity and idealism of the world’s foremost capitalist state. As he recounted in 2007, he took advantage of a major opportunity: “I had finished my O’Levels [sic] in 1962 at the senior secondary school, Old Kampala. I was one of over 20 students who received scholarships to study in the US.”

The elder Mamdani entered the University of Pittsburgh. “The scholarships,” he recalled, “were part of America’s independence gift to Uganda. In the language of that period, I was among those who could claim to have literally eaten the fruit of independence. Certainly, without a successful struggle for independence, I would not have got the higher education that I did.” And without the generosity of the United States, he might never have developed the notion that he needed to play a role in the class struggle.

His initial plan, however, had nothing to do with such matters: “I came here,” he said in 2013, “to be an electrical engineer…. I came to do Electrical Engineering, and this being America, I had to do electives. I had to do all kinds of things but science. I ended up doing all kinds of courses—music, art, Roman catacombs, philosophy, history…so I changed.”

The change in Mahmood Mamdani’s thinking first manifested itself as a simple act of solidarity in a just cause. During his first year at the University of Pittsburgh, he said, “a friend of mine took me to a SNCC [Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee] meeting, six or seven months after I was here. At the end of the meeting they announced that buses were going to Montgomery, Alabama, to demonstrate. I went there, got beaten up, thrown in jail.”

In another interview, he provided more details.

One of my first activities as a student was to participate in the civil rights movement in the US. In less than a year, I was among bus loads of students going from northern universities to march in Birmingham, Alabama, in the south. We marched through secondary schools, singing songs such as ‘Which side are you on, boys, which side are you on?’ and ‘We shall overcome’, and asking students to leave classes and join us. As we moved downtown, police on horseback and motorcycles, wielding metal-studded batons, jumped at us. Scores of other students and I were thrown in jail.

When he was allowed to make the proverbial one phone call from the Birmingham jail, Mahmood Mamdani called the Ugandan ambassador in Washington, DC, Dr. Solomon Bayo Asea. The ambassador did not share Mahmood’s enthusiasm for justice and instead asked him angrily: “What are you doing interfering in the internal affairs of a foreign country?” It was a good question. Mahmood Mamdani was taking advantage of the kindness of the country that had welcomed him and enabled him to attend a first-class university by decrying that country for its oppression. And while there were numerous injustices involved in segregation, it was ironic that he was joining protests for a group of people who generally had a higher standard of living than most of his own countrymen back in Uganda enjoyed.

Mahmood Mamdani answered the ambassador with an appeal to idealism: “‘This is not an internal affair. This is a freedom struggle. How can you forget? We just got our freedom last year’, was my response. I had learnt that freedom knew no boundary, certainly not that of colour or country.” In a different interview, he recalls being even sharper with the hapless envoy: “What? We just got our independence! This is the same struggle. Have you forgotten?” Nevertheless, Asea got Mahmood Mamdani out of jail after one night.

The matter, however, was not closed. “Two or three weeks later,” the elder Mamdani recounted, “I was in my room. There was a knock at the door. Two gentlemen in trench coats and hats said, ‘FBI.’ I thought, ‘Wow, just like on television.’ They sat down. They were there to find out why I had gone—because this turned out to be big—it is after Montgomery that King organized his march on Selma.”

Mahmood Mamdani described a comic scene that unfolded when the FBI agents tried to determine if the young Ugandan Indian was a Marxist. As it happened, the quickly radicalizing student says that he had not yet even heard of Karl Marx:

They wanted to know who had influenced me. After one hour of probing, the guy said, “Do you like Marx?”

I said, “I haven’t met him.”

Guy said, “No, no, he’s dead.”

“Wow, what happened?”

“No, no, he died long ago.”

I thought the guy Marx had just died. So then, “Why are you asking me if he died long ago?”

“No, he wrote a lot. He wrote that poor people should not be poor.”

I said, “Sounds amazing.”

I’m giving you a sense of how naïve I was. After they left, I went to the library to look for Marx. So that was my introduction to Karl Marx.

The FBI, Mahmood Mamdani claimed, had unwittingly introduced him to Karl Marx. He began working hard to make up for his former ignorance: “Then, of course, I took a class on Marx. Couldn’t just get Marx out of the library. But, basically, it is the US—the civil rights movement and the anti-war movement—which gave me a new take on my own experience, and on the Asian experience in east Africa. It gave me a way of rethinking my own experience of growing up in east Africa and growing up in an Africa with a lens crafted by the civil rights movement.”

Mahmood Mamdani was now embarked upon the pathway that would lead him to become an internationally renowned leftist academic, and his son the first Marxist mayor of New York City. Ironically, his introduction to Marxism came from his experiences while benefiting from the generosity of the nation that was Marxism’s most formidable target and foe.