[Order Michael Finch’s new book, A Time to Stand: HERE. Prof. Jason Hill calls it “an aesthetic and political tour de force.”]

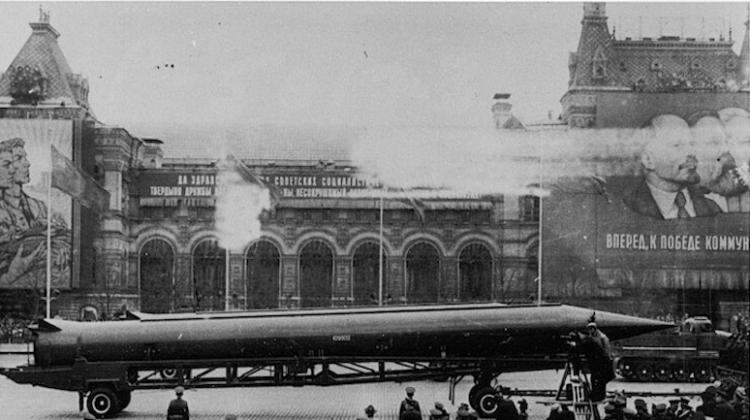

Americans today are accustomed to the fact that there is a hostile Marxist nation seventy-five miles off the coast of Florida, which was the site of one of the most notorious incidents of the Cold War, the Cuban Missile Crisis. Inhabiting much of south Florida are refugees from the Communist regime who are grateful for the freedom that living in America offers them. But the hostility between Cuba and the United States remains relatively newly minted; long before the Cold War, there were even efforts to bring Cuba into the United States, and those efforts contain lessons for Americans of our own age.

Talk of the U.S. annexing Cuba began in earnest after the Mexican War, when the U.S. made immense territorial gains in the Southwest. Some Southerners believed that they had been cheated out of their fair share of the lands that Mexico ceded to the U.S.; Southerners as well as Northerners had fought in the Mexican War and deserved, they felt, equal representation in

the division of its spoils. The South’s Manifest Destiny, they concluded, lay not in the West, but even farther South.

Calls to acquire Cuba, at that time a Spanish colony, either by peaceable means or by force, and admit it to the Union as a slave state grew more insistent throughout the presidency of Millard Fillmore (1850-53). In his annual message to Congress of December 6, 1852, the president replied judiciously that he would consider Cuba’s “incorporation into the Union at the present time as fraught with serious peril. Were this island comparatively destitute of inhabitants or occupied by a kindred race, I should regard it, if voluntarily ceded by Spain, as a most desirable acquisition. But under existing circumstances I should look upon its incorporation into our Union as a very hazardous measure. It would bring into the Confederacy,” by which he meant the United States, “a population of a different national stock, speaking a different language, and not likely to harmonize with the other members.”

Fillmore’s warning that the acquisition of Cuba would be unwise because its population was linguistically and culturally different from Americans was entirely uncontroversial in 1852. It was taken for granted, and would be for over a century thereafter, that while immigrants to the United States were welcome, they were expected to assimilate and adopt American values. Cuba becoming a Southern state of the United States would all at once add a large, unassimilated, and culturally distinct population to the United States; the potential for strife of all kinds would have been enormous.

Nowadays Fillmore would be roundly condemned as racist for saying such a thing, but really, there was nothing unreasonable or hateful (or racist, for that matter) about his assumption that a nation’s people should have a common culture and language, as well as shared values. The rejection of this idea has brought immense division to American society, and it is taken for granted all over the world that nations can justifiably make efforts to preserve their national character. That idea becomes “racist” only when the nation in question is in the Western world.

Fillmore also believed, almost certainly correctly, that annexing Cuba would upset the Compromise of 1850, the fragile agreement that was holding the nation together at that time: “It would probably affect in a prejudicial manner the industrial interests of the South, and it might revive those conflicts of opinion between the different sections of the country which lately shook the Union to its center, and which have been so happily compromised.”

Fillmore’s reservations were entirely reasonable; only a few years later, however, the former president would mount a third-party bid to return to the White House as the candidate of the American Party, which was actively nativist and anti-immigrant, and proclaimed its “eternal hostility to Foreign and Roman Catholic influence.”

Fillmore’s message to Congress was more measured, and his becoming the American Party standard-bearer was unfortunate. Nowadays, concern that immigrants assimilate and adopt American values is routinely conflated with nativism and general hostility to immigration as such; no one remembers President Millard Fillmore today, except for his uncanny resemblance to Alec Baldwin, but his career trajectory does nothing to dispel the impression that opposition to mass unvetted migration is simply racist and xenophobic.

If Cuba had become part of the United States in the mid-19th century, the U.S. would have been spared a great deal of trouble in the mid-20th. Still, annexing Cuba would have invited all manner of other troubles, and likely proven Fillmore’s concerns to be correct. The impact on migration policies adopted over a century later might have been immense.