Of all the sites in American history, perhaps Valley Forge is most associated with winter. Thus it seemed somehow appropriate that, on the shortest day of the year — and first of winter — I should explore the grounds on which the Continental Army spent the six months from December 1777 to June 1778 in its most commemorated winter encampment of the Revolutionary War.

Located in the suburbs of Philadelphia, Valley Forge stands as a testament to the dedication of the thousands of individuals who sacrificed themselves for the sake of liberty, their homeland, and their posterity. And as America prepares to celebrate its 250th birthday, Valley Forge itself prepares to celebrate its 50th birthday as a national historic site; President Gerald Ford signed legislation creating Valley Forge National Historical Park on July 4, 1976 — our nation’s bicentennial.

Death and Disease

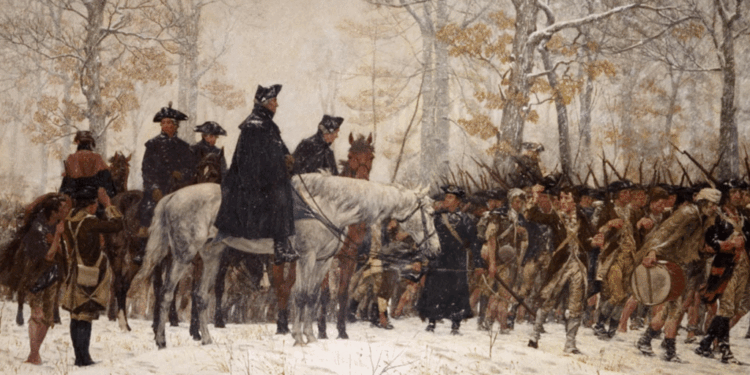

As I gazed across the barren land, the leaves having long since fallen from the trees, the tableau seemed appropriate. After he had to surrender Philadelphia to the British in September 1777, General George Washington selected Valley Forge for his winter encampment due to its geography — close to the colonial capital but far enough away that the enemy could not show up unannounced. The site’s elevation also helped discourage British attacks, a fact I recognized as the wind whipping the bluffs above the Schuylkill River heightened the winter cold and gloom.

During my visit, I soon learned that, contrary to popular perception, the winter of 1777-78 was not particularly cold or snowy. In reality, the Continental Army’s weather woes came more from rain, sleet, and mud than from bitterly cold temperatures. With plumbing and sanitation ranging from crude to nonexistent, the soldiers, perpetually hungry from their meager rations, also faced disease. Dysentery and typhus ran rampant, and a second outbreak of smallpox in as many years forced Washington to order inoculations.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the impromptu huts the soldiers made for themselves upon entering the camp proved cramped and insufficient. Modern replicas placed at various locations around the National Park appear rough for one or two soldiers, let alone the number packed into the more hastily and crudely built originals.

The inscription at the top of the War Memorial in the center of the park uses words from Washington himself to describe the dedication of those encamped with him at Valley Forge: “Naked and starving as they are, we cannot enough admire the incomparable patience and fidelity of the soldiery.”

Reasons for Hope

In time, of course, both the weather and the military environment would brighten. News of America’s alliance with France would arrive in the spring of 1778, prompting a series of celebratory maneuvers across the parade grounds at Valley Forge. More importantly, the alliance brought the prospect of additional supplies that would prove crucial in the years ahead.

Training and morale improved too. Baron Friedrich von Steuben, a Prussian soldier recommended to Washington by Benjamin Franklin, helped instill discipline among the heretofore ragtag soldiers, drilling them regularly during their time at Valley Forge (and swearing frequently while doing so). Over time, a fighting force, nearly a third of which did not speak English as their first language, slowly transformed into something more approaching its name: a Continental Army.

The six months it spent at Valley Forge in late 1777 and early 1778 proved a testing crucible for the Army and the nation as a whole. Whether in winter or any other season, visitors traveling near Philadelphia would be wise to spend a few hours exploring this hallowed ground to ponder the sacrifices prior generations made on our behalf so we might be free.

Valley Forge National Historical Park is located approximately 20 miles northwest of Philadelphia, near the intersection of Interstate 76 (the Schuylkill Expressway) and the Pennsylvania Turnpike. Park grounds are open from 7 a.m. to dark; visitor center open 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. daily; Washington’s Headquarters open 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. daily in summer, 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. weekends in winter. For more information, visit https://www.nps.gov/vafo/index.htm.