Not long ago, I advised Federalist readers to make an effort to dig into our nation’s history, specifically that of the Revolutionary period, ahead of the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence next July. As luck would have it, within days of submitting that piece, I learned about a new exhibit that allowed me to take my own advice.

“The Two Georges: Parallel Lives in an Age of Revolution” profiles the two leading figures in the struggle for independence: Britain’s King George III and George Washington, leader of the Continental Army (and future president), who defeated George III’s troops. The Library of Congress’s yearlong exhibit, which features archival material from its own vaults and those in Britain, goes behind the myths and legends surrounding the two leaders, choosing instead to examine the flesh-and-blood humans who defined a new nation’s attempt to come into its own.

Similar English Gentlemen

For all the differences that came between these two individuals on opposite sides of the Atlantic, “The Two Georges” also highlights their similarities. Both were born in the 1730s (Washington in 1732, George III six years later), and both suffered the loss of their father early in their lives.

The commonalities extend beyond age and family structure to a shared culture, albeit from a distance of more than 3,000 miles. A portrait of George III’s father, Frederick, Prince of Wales, painted by Bartholomew Dandridge, speaks to the shared links between the two Georges. Dandridge’s close relative Martha married the “other” George, showing how the two ran in the same proverbial circles.

The Georges also took an interest in many of the same pursuits. While American schoolchildren learn of Washington’s early career as a surveyor and draftsman, and his agricultural work running Mount Vernon, few on this side of the Atlantic recognize that George III also took an interest in drafting and agriculture. In a fascinating display, the exhibition shows each George’s personal copy of The Gentleman Farmer side by side, indicating the Enlightenment theories and techniques the men studied to improve their farms — and their lives in general.

Disparate Dispositions

While the exhibit shows their commonalities, it also hints at their differences and how those differences changed the course of history. Each George faced difficulties raising children (in Washington’s case, as a stepfather rather than a biological one), but the English king proved the more headstrong of the two. George III famously forbade his five daughters from marrying, so enjoying their company that he refused to forego it, prohibiting them from moving out of his household.

That type of familial conflict — he upbraided his son, the future George IV, for his profligacy — hinted at the approach George III would take toward the American colonies. While he wanted to preserve the bonds between Britain and America, he also felt the need to “lay down the law,” lest other colonies get ideas about breaking away from the mother country. In referring to “the dismemberment of America” from the British Empire, George III presaged the “domino theory” that defined America’s involvement in the Vietnam War two centuries later — both to tragic effect.

Giving Up Power

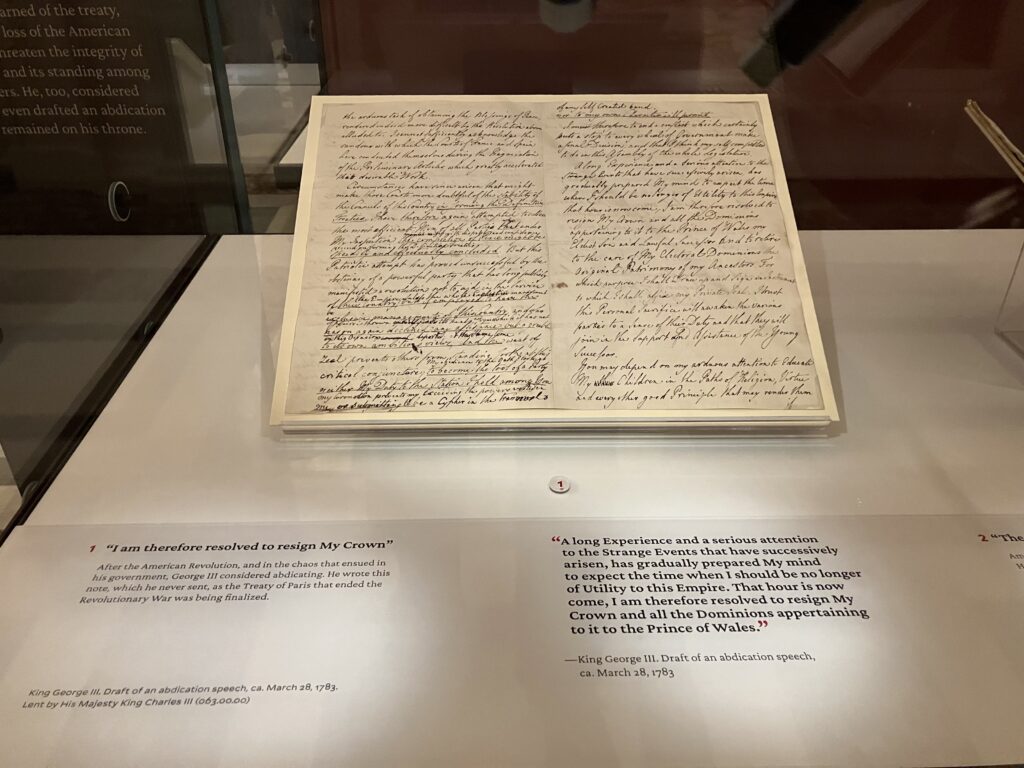

Yet when the Revolution’s success led Britain to lose her largest colony, George III contemplated an action that might have seemed unthinkable to the Founding Fathers, who viewed him as a tyrant. Arguably the most compelling document of the exhibition comes in the form of an original draft of George III’s abdication speech:

A long experience and a serious attention to the strange events that have successively arisen has gradually prepared my mind to expect the time when I should be no longer of utility to this Empire. That hour is now come; I am therefore resolved to resign my Crown and all the Dominions appertaining to it to the Prince of Wales.

George III never delivered the speech, of course; he remained on the throne until his death in 1820, even after mental incapacity resulted in a Regency period when his son reigned in his stead.

But the fact that George III contemplated such a radical step — one that I heard about for the first time through this exhibition — speaks to the effect that American independence had on his psyche. (In a separate document, Gouverneur Morris wrote that, during one of his periods of mental illness, George III fashioned himself as George Washington, a fact that reinforces this point.)

George III famously proclaimed Washington “the greatest man in the world” for being willing to give up office and power voluntarily. The king’s own willingness to consider doing the same, even if rooted in his own sense of inadequacy, suggests he held power more lightly than most Americans have traditionally been led to believe.

With its rich trove of archival documents from the Royal Collection and the Library of Congress — including the original copy of General Washington’s Continental Army commission, on display through June 2025 — “The Two Georges” allows visitors to view these two historically significant individuals as they were, rather than as the one-dimensional caricatures often portrayed in history books. In so doing, it allows 21st-century Americans to reexamine the events behind the Revolution in a far different light.

“The Two Georges” runs through March 21, 2026, in the Library of Congress’s Jefferson Building. The Library is open Tuesday through Saturday; admission is free, but timed-entry tickets (available online) are required.