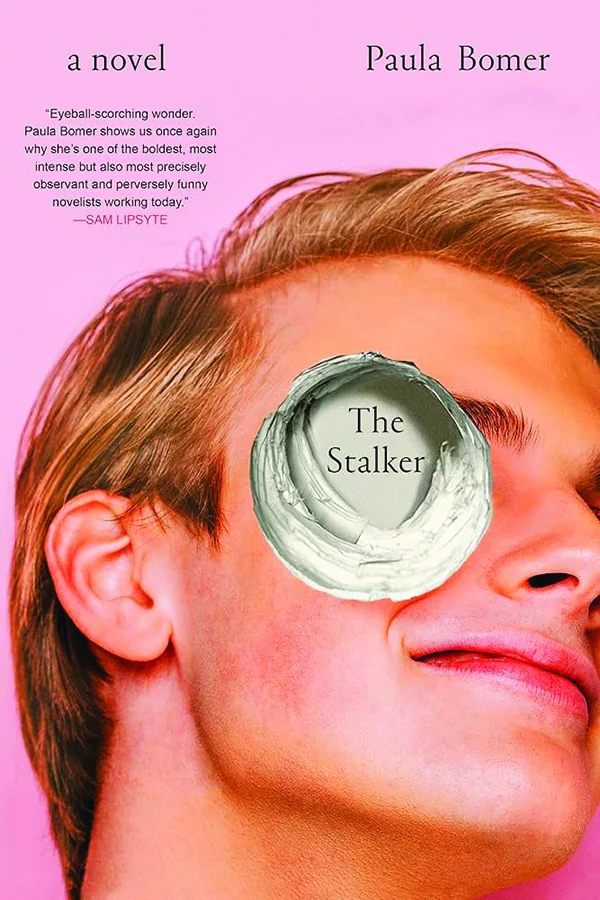

Paula Bomer’s novel The Stalker is a poorly written book. The narrative voice is dull. It observes narrowly, always telling when showing would suffice. Its descriptions are crude, such as when it renders a woman’s sagging breasts as “extra butt cheeks.” The dialogue is flat, exchanged between characters who are more of a collection of debilitating traits, traumas, and neuroses than containers of multitudes, let alone personalities. By the standards of literary fiction, The Stalker may be the worst-written book of the year.

Of course, to state it as plainly as that is also to accept Bomer’s motivation in capturing a particular form of solipsism on its own terms, and her mastery in doing so. It is barely enjoyable because it must be. For her to encase her narrative in elegance and wit, or to leaven its mordant delusions with pathos or more overt comic beats, would mean to deprive it of its bite. A character on the level of Robert Doughten “Doughty” Savile, an antihero with a greater degree of anti than of heroism, deserves nothing less. Just as the reader deserves nothing more.

Doughty is a predator with some very much conscious echoes of past icons of the type — Bateman, Ripley, Humbert, even Caulfield — just not very clear ones. Walking among this Pantheon of literature’s male malcontents, Doughty cuts a figure closer to a mediocre cousin they see once every 15 years. He has the charm of Dennis Reynolds of It’s Always Sunny, the intellect of Paul Rudd’s Lothario camp counselor in Wet Hot American Summer, and the instincts of Ted Bundy. In combination, he is, before anything else, a Horatio Alger striver turned inside out.

He comes from old money in Connecticut, making much of the old part as the money dwindles. From his father, he inherits a cynical, misogynistic outlook and half a million dollars in debt, while his deferential mother endlessly enables him. He treats his friends like rivals and women like marks. To the extent that he has any talents, they are in exploiting weakness and wearing people down until they surrender to his whims. He does not need to read The 48 Laws of Power or The Game. He is “the game” incarnate. All he needs is his father’s advice, such as “Every woman loves a fascist.” On that, he does an impressive amount of damage, failing upward in early-1990s New York City. He is equal parts unstoppable force and immovable object.

The Stalker has less of a plot than it does an appetite that needs constant sating. And the “stalking” in question is less any one person than the landscape itself. Like any skilled grifter-abuser, Doughty cycles and recycles between different targets and habits. He invades the lives of three women — a middle-aged, an alcoholic editor, a bartender whom he had earlier exploited in his hometown, and an addict living in Tompkins Square Park. In the case of the first, he is let into her loft in Soho and simply never leaves in spite of many ineffectual attempts from its owner. There, we are made privy to his harsh yet pothole-deep worldview. “It was important to know what was going on in the world,” the narrator, who I have no reason not to presume is Doughty speaking in the third-person, muses. “The news was grim. The economy was bad. Clinton, a white-trash embarrassment to the United States, had replaced George Bush. … He missed Bush. Bush was a Yale man. So he didn’t know things, like that they spoke German in Austria. But who cared?”

When not ingesting drugs, having degrading sex, masturbating, or taking over lofts from their rightful owners, Doughty is extolling his literally encyclopedic knowledge cribbed from his prized Encyclopedia Britannica set, or quoting bits from George Carlin from memory. Doughty sees Carlin with a Nietzschean halo, one of a few role models aside from his father and Mr. Miyagi from The Karate Kid. “He’s not vulgar, Mom. He’s a genius. And like me, he uses language that is necessary.” Such language involves condemning people for crimes of low social standing or racial makeup. Often both. (“After he dropped her off at her broken-ass-looking house … and finding out her last name, Murphy, of course she was part Mick.”) On top of everything else, Doughty is the “equal-opportunity offender” par excellence.

Ultimately it is supposed to be Doughty who is the butt of the jokes. These jokes come in the form of interventions by reality against his delusions. A banker tells him that his inheritance is three figures, not six. The “lazy” woman he’s sleeping next to in the loft turns out to be days into decomposition. It aims for pitch black deadpan, but settles more often than not for “fluency in sarcasm.” At a sustained delivery, the reader feels as exhausted by it as Doughty’s victims. And delusion always bests reality, even down to the physical comedy conclusion.

ANDREA DWORKIN’S UNFINISHED BUSINESS

Bomer’s immersive yet ridiculous portrait of masculinity is designed as a prestigious complement to grim, usually female-targeted comfort content, such as You and true crime. Here is your villain, The Stalker declares, in the highest possible definition. But being so long mired in Doughty’s headspace compels the reader to see certain weaknesses in that content. The problem is not simply that it functions on a formulaic villain/victim binary, whatever its pretensions to nuance, or that it imbues the villain with near-vampiric powers. It is that the villain remains central, and the victims are at best peripheral and at worst sacrificial. It’s difficult not to see the women in The Stalker as grist for its antihero’s gaze.

If this is a critique of men, or a certain exaggerated but real sort of man, it is so extreme, unbelievable, and long-winded as to be a failure of critique. Doughty’s toxic male gaze is so single-minded in its scope that it reveals something like a skill: an exacting attention to detail. Combine that with this status obsession, his information fetish, and his sensitivity to cultural mixing, and you have a remorselessly sociological frame of mind. The time he spends with each of his victims doubles as demonic field research in failure modes of the urban female. Much is made of Doughty’s lack of talent, though it’s a fair assumption that talent would have spread his hazards on the macro level. The line between social science and energy vampirism is a faint one.

Chris R. Morgan writes from New Jersey. His X handle is @cr_morgan.