A new generation of anti-abortion advocates is filling critical gaps in women’s healthcare through grassroots institutions typically scorned by the mainstream medical community: pregnancy resource centers.

Pregnancy resource centers, or PRCs, have increasingly served as mini medical centers for women experiencing unplanned pregnancies since the Supreme Court ruled in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization in 2022 that there is no constitutional right to abortion, a period that has also seen more hospitals close their maternity units.

But PRCs, traditionally called crisis pregnancy centers, have been part of the anti-abortion arsenal since Roe v. Wade was decided in 1972. Through the decades, PRCs have been subjected to a multitude of criticisms, particularly that they do not treat the medical needs of women, disseminate false health information, and trick or shame women out of having abortions.

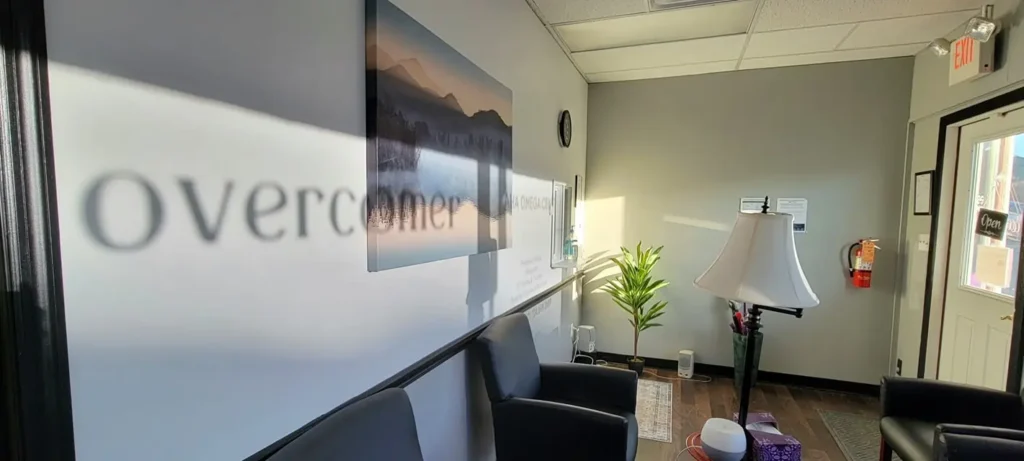

Rebekah Cohen Morris told the Washington Examiner that this is far from the truth, at least for her center, the Aim Women’s Center, in Steubenville, Ohio.

Morris worked in immigration and housing activism before becoming the director of Aim in 2023. She says she had never even stepped foot in a PRC before coming to Aim.

“I’d always been pro-life, but I had my own hesitations,” Morris told the Washington Examiner. “I didn’t really know what they do at pregnancy centers. You know, you hear all the negative stereotypes.”

Aim was on the verge of bankruptcy before she took the reins. Now, the center has a registered diagnostic medical sonographer offering ultrasounds through all 40 weeks of pregnancy, a labor and delivery nurse, and an OB-GYN medical director.

Their medical team offers preeclampsia screening during and after pregnancy, as well as testing for STIs such as gonorrhea and chlamydia, all free to patients. They also typically see patients within one or two weeks, much less than the wait to see an OB-GYN in a region that struggles to keep doctors.

“We also have a shortage of sonographers in the area and OB-GYN care, so a lot of women aren’t even able to get in to see a doctor early on in their pregnancy,” Morris said. “So they’re at least able to come here early on, confirm pregnancy, confirm viability, confirm that it’s an intrauterine pregnancy, not an ectopic pregnancy.”

Bridging the gaps in medical care

PRCs have traditionally provided parenting classes for mothers and fathers, as well as material needs to support new families, ranging from diapers and baby clothes to big-ticket necessities such as cribs, strollers, and car seats.

But in addition to those material and educational concerns, a growing number of PRCs offer health services for pregnant women, particularly in areas with a widening dearth of obstetric and gynecologic care.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated in 2022 that 24 in every 100,000 women die annually due to pregnancy-related complications, but that’s a hotly contested statistic. The World Health Organization estimates that the U.S. maternal mortality ratio is closer to 17 per 100,000, still significantly higher than most other developed countries.

On top of that, hospitals across the country, particularly rural hospitals, have been slowly closing their maternity wards for years.

A December 2024 study from the University of Minnesota found that, by 2022, 52% of rural hospitals no longer had maternity wards, compared to 36% of urban hospitals. Between 2010 and 2022, 537 hospitals across the country discontinued their obstetrics programs.

A Becker’s Hospital Review report in January last year found that 37 more hospitals planned to close in 2024.

Sarah Bowen runs the Promise of Life Network in New Castle, Pennsylvania, approximately an hour north of Pittsburgh. Bowen told the Washington Examiner that three hospitals in her region have either shut down their obstetrics wards or closed their doors entirely.

Traveling to Pittsburgh or Erie for medical care is enough for some women to delay or even skip critical prenatal visits.

Bowen’s clinic attempts to fill the vacuum by focusing on early maternal health, offering initial diagnostics and prenatal vitamins, as well as education on the importance of OB visits and the dangers of smoking and alcohol during pregnancy.

“A lot of women who are in the community where our pregnancy center is located are going to have to travel, not insanely far, but if you don’t have a car, you don’t have reliable transportation, it’s a burden to try and get help,” Bowen said.

PRCs by the numbers

The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists warns that PRCs falsely represent themselves and their staff as medical professionals and provide false information about the medical risks of abortion versus pregnancy.

But about 16% of the nearly 63,000 people who staff the 2,750 pregnancy centers across the United States are licensed medical professionals, according to the anti-abortion research group the Charlotte Lozier Institute.

Seven in 10 PRC workers are solely volunteers, but more PRC medical personnel are paid rather than volunteers.

While these facilities do not have the resources or expertise of hospitals or major medical centers, many offer a limited array of maternal and other women’s health services, even if it isn’t their primary focus.

More than 82% of PRCs offer diagnostic ultrasounds for early pregnancy, a 3 percentage point increase since 2019. ACOG asserts that PRCs use these to shame women into keeping their pregnancies. Diagnostic ultrasounds, though, are part of the standards of care to determine pregnancy viability.

Roughly 36% of PRCs in 2022 provided STI testing, up by 6 percentage points since 2019. STI treatment is also up by 7 percentage points since 2019, with about 28% of centers offering treatment either for free or for a small fee.

Bowen said that STI services are part and parcel of quality women’s healthcare, regardless of whether a patient chooses to keep her pregnancy.

“To have them come to the pregnancy center and confirm their pregnancy and learn about resources, learn about health, and get those first foundational building blocks in how to have a healthy pregnancy; that’s huge,” Bowen said.

More than 1 in 4 centers offer lactation assistance, up from 1 in 5 in 2019. About 100 PRCs nationwide offer full-service prenatal care, nutritionist or dietitian services, and well-woman exams.

Nearly all centers, 96%, offer adoption information to their clients, and about 5% have an adoption agency on site.

“Look at her holistically”

Because of their limited resources compared to full medical facilities, PRCs often work with other community partners to connect their patients with social services to fill other critical needs.

Bowen says that her center offers a great deal of referral services for food or housing insecurity, as well as mental health services.

“We screen for domestic violence and sex trafficking and suicidal ideation and other mental health concerns, and we offer referrals for all of that,” said Bowen. “So we’re going to look at her holistically and say, what does she need? What are her needs right now and how can we address those?”

The Ohio River Valley, where Bowen and Morris both operate, is a region heavily affected by the opioid epidemic, so they have strong relationships with community partners assisting with substance abuse treatment.

Although Morris’s facility does not directly provide services for those struggling with substance abuse disorders, Aim is opening a maternity home this summer for women who have been 30 days sober and are experiencing housing insecurity. Women can stay there with their babies up to a year after birth.

Morris says she hopes within the next few years to establish new maternity homes for mothers in recovery from substance abuse disorders that specialize in providing withdrawal care for mothers and their infants.

“I think because that problem has continued, and if not continued, also intensified the fact that we are ramping up services so that we aren’t just doing what we’ve done for 20 or 30 years,” said Morris. “We’re now saying it’s going to take a more holistic approach to really help women choose life.”

How PRCs treat abortion

Julie Tompkins, patient services director at Blue Ridge Pregnancy Center in Lynchburg, Virginia, told the Washington Examiner that they have five nurses on staff. One of the nurses’ responsibilities is to inform patients about what to expect during the abortion process and what complications they may face afterward, particularly for medication abortion.

Recent studies have found that women who choose medication abortion are at a higher risk of infection and hemorrhage than those who opt for surgical abortions. Medication abortion patients also report having higher levels of pain and bleeding than they are told to expect by their medical professionals.

Blue Ridge also provides physical and mental post-abortive care for women, including grief counseling for those who regret their abortions. Tompkins said that about 90% of their patients who had abortions say they feel guilt or shame for their decision.

But Tompkins noted that even patients who choose abortion after visiting Blue Ridge often come back if they find themselves unexpectedly pregnant again.

“I just had a patient last week and she had an abortion earlier this year, and came back with a second pregnancy now, and things are different now, and she’s parenting this time,” said Tompkins. “They know that it’s a safe place, that they’re not judged, and that we love them no matter what.”

Becky Sheetz, CEO of Life First, with two centers in Manassas and Woodbridge, Virginia, prides herself and her operation as being able to share the gospel with their patients if they are willing to bring faith into their discussion about options.

When asked about the claims that PRCs, especially explicitly Christian centers, intensely pressure women not to have an abortion, Sheetz said the “idea breaks our hearts.”

“If we are, with permission, explaining the abortion procedures and she says ‘I can’t do this. I can’t hear anymore,’ we stop talking,” said Sheetz. “We’re not going to force her to listen to something that she doesn’t want to listen to.”

Each center is different, but PRC directors told the Washington Examiner that coercive practices are not part of their facilities’ operations.

Morris attributed the determination of the anti-abortion movement to combat negative stereotypes to the generation of millennials and Gen Z taking more prominent grassroots leadership roles, particularly at PRCs.

“It’s not just like ‘good luck, glad you’re pregnant, glad you’ve chosen life,’” said Morris. “We’re just loving the women. A lot of them are just so alone and their reason for wanting abortion is feeling like they’re just going to do this all alone in poverty, in a bad relationship, with no support. We say we’re going to be here for you.”