Progressivism, undeniably, is the ideological backbone of much, if not most, of the rhetoric and policy of the modern Democrat Party.

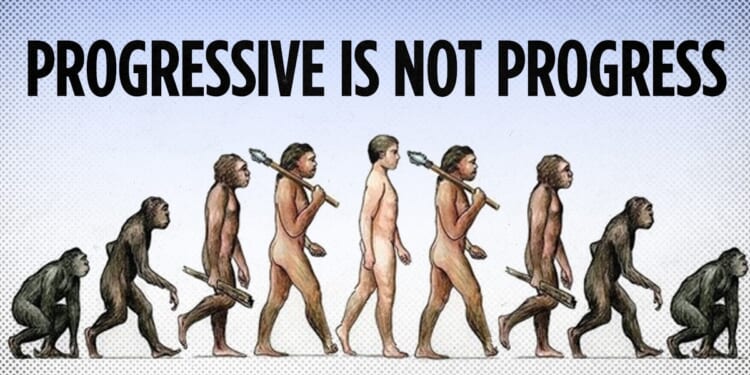

It rests on the assumption that humanity’s knowledge and moral clarity improve with time, rendering the past largely irrelevant at best. This belief in linear progress drives a worldview that dismisses historical traditions, institutions, and values as outdated, favoring relentless reform to align society with contemporary ideals. While progressives argue this approach corrects historical wrongs, their wholesale rejection of the past risks eroding the foundations of a stable society, ignoring the enduring wisdom embedded in time-tested systems.

This is why they dismiss Western civilization as a ruined relic of the past, they deny the role of Christians and Jews in the construction of the modern world, deny the fact that capitalism has brought a higher standard of living to every nation it has touched, believe empirical reasoning is inferior to emotional reasoning, and reserve a special loathing for white people of European descent for their penchant for exploration and colonization (and improvement) of the world.

It is also the reason they hate the Constitution and its enshrinement of transcendent principles, and they would prefer it to be “living.” Justice Antonin Scalia’s observation that the Constitution says what it says, and it doesn’t say what it doesn’t say, is lost on them.

The progressive mindset views history as a series of mistakes to be overcome rather than a source of insight. Enlightenment-era philosophies, which championed reason and science as engines of perpetual advancement, fuel this perspective. Progressives often assume that modern knowledge — whether scientific, social, or moral — surpasses the understanding of previous generations. This leads to presentism — a tendency to judge historical figures and institutions by today’s standards, ignoring the context in which they operated. For instance, the push to remove statues of Founding Fathers or reinterpret their legacies often stems from a belief that their actions, tied to slavery or other moral failings, disqualify their contributions from relevance. Yet this overlooks the complexity of their era and the principles they established, which remain foundational to modern governance.

With progressivism, G.K. Chesterton’s parable of the fence is always in play. Progressives are ready to tear down every fence, even as they admit they have no idea why it was put up in the first place.

This rejection of the past manifests in policy as well. Proposals like the Green New Deal or calls to “reimagine” institutions such as the Electoral College or law enforcement reflect a conviction that new frameworks, informed by current knowledge, are inherently superior. Progressives argue these reforms address modern challenges like climate change or systemic inequality, but their haste to dismantle longstanding systems often disregards why those systems were created. The Electoral College, for example, was designed to balance regional interests in a diverse nation — a concern as relevant today as in 1787. Dismissing such structures as relics risks destabilizing the delicate equilibrium they maintain.

Culturally, progressivism’s emphasis on evolving norms — redefining concepts like gender, marriage, or free speech — prioritizes present sensibilities over traditions that have shaped societies for centuries. While advocates claim this reflects moral progress, it assumes modern values are universally correct, ignoring the possibility that rapid shifts could have unintended consequences. Traditional frameworks, although imperfect, often emerged from generations of trial and error, balancing the complexities of human nature in ways that new ideologies may not yet fully grasp.

Viewing the world through this lens causes progressives to underestimate or dismiss the value of historical continuity. Thinkers like Edmund Burke emphasized tradition as a repository of collective wisdom, tested by time and experience. By contrast, progressivism’s faith in the present can border on hubris, assuming today’s knowledge is the pinnacle of human understanding. Such a process risks creating a society unmoored from its roots, where change for its own sake replaces careful deliberation.

Again, Chesterton’s parable notes that not all change is necessarily good. Fences have two purposes: first, to keep something in, and second, to keep something out. Understanding which side you are on before tearing it down might be important to your survival.

Progressives will counter that their focus is not rejection but improvement, applying new insights to correct historical injustices like slavery or discrimination, yet their approach often favors utopian visions over true, hard lessons learned and pragmatic (and necessary) continuity.

A balanced perspective would integrate modern knowledge with respect for enduring principles, recognizing that while the past is not infallible, it offers wisdom that the present cannot always replicate or validate.

But “balanced” is not a term I would use to describe hysterical, humorless, and fantasy-prone progressives of today.