Order Robert Spencer’s new book, Holy Hell: Islam’s Abuse of Women and the Infidels Who Enable It: HERE.

As nationwide protests threaten finally to end the Islamic Republic of Iran, which has plagued the world for 46 years, it is useful to remember how it was established in the first place. It is largely the handiwork of Jimmy Carter, the 39th president of the United States.

In 1978, as protests against the Shah engulfed Iran, Carter offered no help to his ostensible ally. Instead, he dithered, and ultimately abandoned the Shah to his fate, in part because neither the president nor any of his staff could decide exactly what to do instead — but mostly because many in the Carter administration admired Khomeini, and didn’t want to do anything to harm him or his movement.

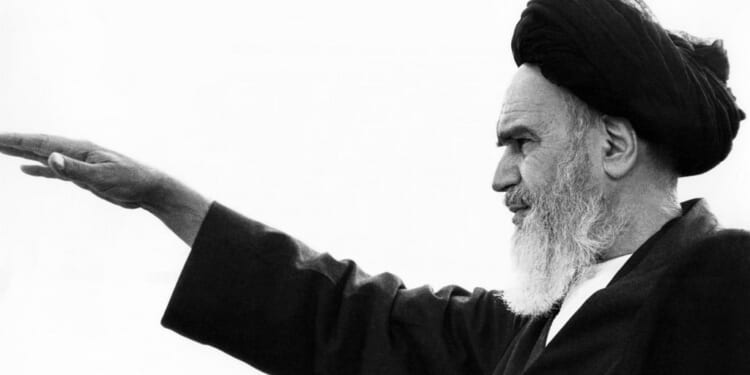

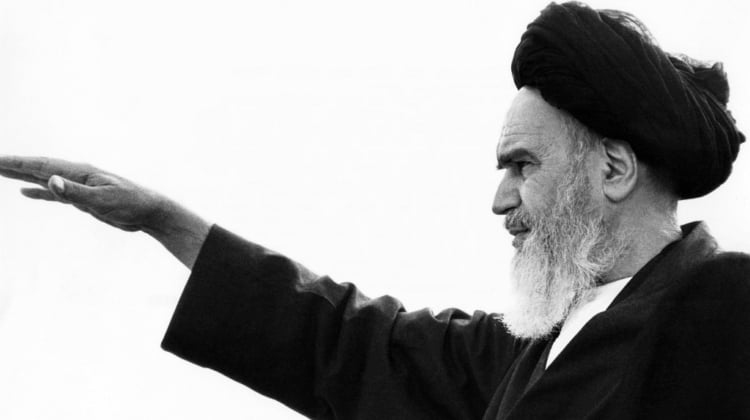

As The Complete Infidel’s Guide to Iran details, Andrew Young, the U.S. ambassador to United Nations, said, “Khomeini will eventually be hailed as a saint.” The U.S. ambassador to Iran, William Sullivan, saw the Iranian cleric as a man of peace: “Khomeini is a Gandhi-like figure.” Carter adviser James Bill declared the ayatollah a “holy man” of “impeccable integrity and honesty.”

Carter himself, meanwhile, was ambivalent about the Shah: “When the Shah came here to visit in November of 1977, my first year in office, I knew that he had been an intimate friend of six presidents before me and a staunch ally that provided stability in that region of the world. But I knew also that SAVAK, his secret military service, had attacked some student demonstrators.” The human rights president would not and could not support such a regime.

The Shah, quite understandably, felt betrayed. “The fact that no one contacted me during the crisis in any official way,” he recounted later, “explains everything about the American attitude. I did not know it then—perhaps I did not want to know—but it is clear to me now that the Americans wanted me out.”

The Americans did nothing as the situation continued to deteriorate. The day after Black Friday, workers in Tehran began going on strike; other workers followed suit, and the strikes quickly became a nationwide phenomenon, while demonstrations also continued. Crowds chanted, “Islam, Islam, Khomeini, we will follow you.”

As the chaos spread, the Shah’s government increased pressure on Iraq to exile Khomeini. Saddam Hussein was only too happy to be rid of the charismatic Shi’ite cleric, and so on October 5, 1978, Khomeini left, only to be turned away by Kuwait and to settle ultimately in France, despite his reluctance to live, “so to speak, among heathens.” Among those heathens, he became a darling of the Western media, which began eagerly shining light on events in Iran, thereby hastening the demise of the Shah’s regime.

On November 5, which came to be known as “The Day Tehran Burned,” rioters, egged on by mullahs who preached about the evils of the West, targeted symbols of Western power such as the British Embassy, as well as outposts of secular pleasures such as movie theaters, along with Iranian government and police installations.

The next day, the Shah appointed a military government, but addressed the nation in conciliatory terms on television. Khomeini, however, was in no mood for conciliation. He compared the Shah to a cat trying to lure mice out of their hiding places with soothing words, only to kill them when they emerged, and he renewed his call for the Shah to be overthrown.

And so from France, Khomeini continued to lead the opposition to the regime, sending a steady stream of cassette tapes of his sermons into Iran — sermons that preached the duty of Shi’ites to revolt against oppressors. He called for protests during the Islamic sacred month of Muharram, which fell between December 2 and December 30, 1978. On December 2, two million protesters heeded his call and took to the streets of Tehran, demanding that the Shah step down and Khomeini be allowed to return to Iran.

The protests grew quickly. Within a week, nine million protesters had taken to the streets. On December 28, 1978, the Shah appointed secular opposition leader Shahpour Bakhtiar prime minister, and announced that he and his family would be going on “vacation” outside Iran, with a referendum scheduled for three months hence on whether Iran would keep its shah or become a republic.

On January 4, 1979, Jimmy Carter traveled to Guadaloupe in France for a summit meeting with French President Valery Giscard d’Estaing, British Prime Minister James Callaghan, and West German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt. Carter told the three that the U.S. was withdrawing all support for the Shah and backing Khomeini. “I was horrified,” recalled Giscard, at this abandonment of an ally. “The only way I can describe Jimmy Carter is that he was a ‘bastard of conscience.’”

On January 16, 1979, a tearful Mohammed Reza Pahlavi and his family left Iran. Their promised return never happened; after two and a half millennia, the Persian monarchy was over. It was Jimmy Carter’s most lasting, and damaging, achievement.