Interest in the midterm elections has developed even earlier than usual this cycle, due in large part to redistricting battles. Six states have already taken the unusual step of redistricting between decennial censuses, with several more states actively considering it. Their goal, of course, is to gerrymander U.S. House districts for 2026. California alone may net five extra seats for Democrats, thanks to its new district lines.

What is sometimes forgotten in the restricting debate is the role that immigration plays in distorting representation, effectively worsening the impacts of gerrymanders. Mass immigration distorts both apportionment, which is the distribution of U.S. House seats among states, and also redistricting, which is the drawing of legislative boundaries within states.

The distortion is due to the 25 million noncitizens added to the U.S. population through immigration. Noncitizens include not only illegal immigrants, but also legal permanent residents, guest workers, foreign students, etc. All of these groups show up in census data, but by law they cannot be voters in federal or state elections.

Rather than apportioning U.S. House seats by the number of eligible voters in each state, the current system apportions seats based on the total population of each state, which includes noncitizens. Since some states have far more noncitizens than average, those states get significantly more representatives per eligible voter than do states with smaller numbers of noncitizens.

There is, of course, already some imbalance because of the requirement that each state has to have at least one seat, but immigration exacerbates the problem. For example, in the 2020 Census, the presence of illegal immigrants and their minor children netted California two extra seats, and Texas one extra seat. That benefit to voters in those two high illegal-immigration states came at the expense of voters in Ohio, Michigan, and Idaho, which each have one fewer seat than they would have in the absence of illegal immigration.

But the impact of illegal immigration is actually small compared to the impact of all noncitizens and their minor children. Their presence in 2020 caused nine seats to be shifted from voters in low-noncitizen states to voters in high-noncitizen states. These distortions are expected to increase in the 2030 Census, due to the immigration surge of 2021-2024.

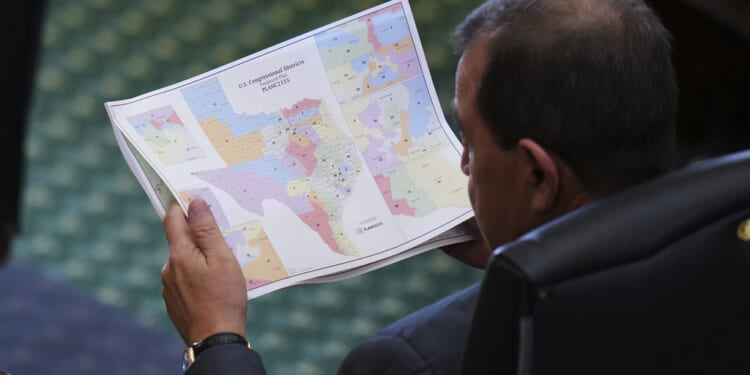

Distortions also occur when determining legislative districts within states. Rather than draw boundaries to equalize the number of eligible voters in each district, states currently equalize the total population in each district. Again, since noncitizens are not distributed uniformly throughout any state, voters who happen to live near noncitizens have more power than voters who do not.

For example, compare the Texas 33rd U.S. House district, where 29% of adults are noncitizens, with the state’s 21st district, where just 4 percent are noncitizens. The 400,000 voting-age citizens in the 33rd district have their own representative, but the representative of the 21st district must be shared with 600,000 voters. “One man, one vote,” this is not.

The same impact occurs in state legislatures. For example, in the group of New York State Assembly districts with high numbers of noncitizens, there are 11.6 representatives for every million voting-age adults. In the group of low-noncitizen districts, however, there are just 9.8 members per million.

Finally, although the distortions caused by immigration would be unfair regardless of partisan implications, the strong correlation between a district’s share of noncitizens and its support for the Democratic Party is difficult to ignore. In the 24 U.S. House districts that are at least 20% noncitizen, Republicans won just four in 2022. Meanwhile, in the 54 districts that are less than 2% noncitizen, Republicans won all but five. Similar results occurred in elections for state legislatures. In other words, by shifting more representation toward places with noncitizens, immigration redistributes political power from voters in Republican areas to voters in Democratic areas.

THE CULTURAL CONSEQUENCES OF RECORD IMMIGRATION

To reduce the distortions, states should consider drawing district lines based on the distribution of citizens rather than the distribution of all residents. To do that, however, the states would need the federal government to collect citizenship data in the next decennial Census. Currently, the government asks about citizenship only in smaller surveys based on a sample, not the full count needed to determine representation.

A more comprehensive solution to the problems caused by immigration is, simply, to reduce immigration. That means controlling the border, deporting illegal immigrants who are already here, and reducing the number of legal immigrant visas that we issue going forward. Under a low-immigration system, distortionary effects on representation would naturally shrink along with the size of the noncitizen population.

Jason Richwine is a resident scholar at the Center for Immigration Studies.