There must be something special in the waters of the Adriatic, because no one creates quite like Italians too. They gave us the world’s most famous movie (The Godfather) and the world’s most famous fairytale (Pinocchio). They gave us the world’s favorite food (pizza) and the world’s most famous painting (the Mona Lisa). They gave us the world’s most famous poem (Dante’s Divine Comedy) and the world’s most famous artists (Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo). They even gave us the very name “America.” (Yes, it’s true — è vero! Look it up!) And, fittingly, they also gave us the world’s most famous fashion designer: Giorgio Armani, who died earlier this month at the age of 91.

Born on July 11, 1934, in the industrial town of Piacenza, Italy, Giorgio Armani grew up far from the glittering runways of Milan. His early years were shaped by a world recovering from war, and his first ambition wasn’t fashion but medicine. He enrolled at the University of Milan, studying to become a doctor, but the call of aesthetics proved stronger than the call of the stethoscope. After his schooling, Armani found himself in a Milan department store arranging window displays with the precision of a painter. It was there that he began to see clothing not just as fabric but as a canvas for ideas.

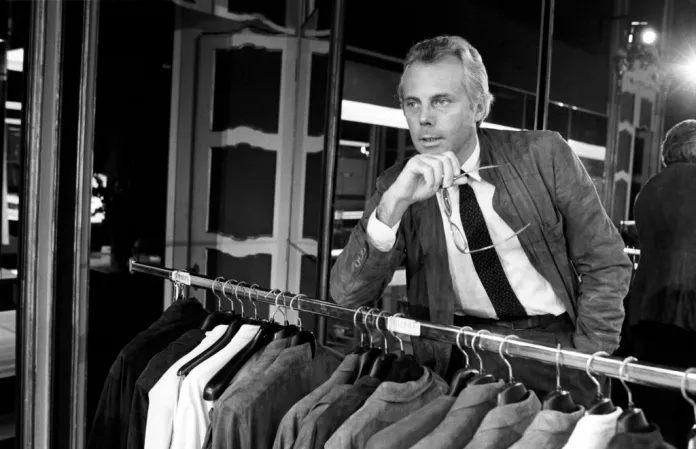

His real education came under the tutelage of Nino Cerruti, where Armani honed his craft designing menswear. Cerruti’s atelier was a crucible for Armani’s burgeoning genius, teaching him the alchemy of cut and cloth. By 1975, with his partner Sergio Galeotti, Armani launched his eponymous label, a bold gamble that would redefine luxury. His first collection was a revelation: soft-shouldered suits that draped like a second skin, blending Italian craftsmanship with a relaxed modernity. The fashion world, accustomed to rigid tailoring, was stunned. Armani had dared to make men’s clothing feel free.

Women, too, fell under his spell. Armani’s designs for women borrowed from menswear’s authority — crisp blazers, tailored trousers — but infused them with a fluidity that empowered rather than constrained. “I was the first to soften the image of men and harden the image of women,” he wrote in his 2015 book, a line that captures his knack for upending convention. Richard Gere’s Armani wardrobe in American Gigolo (1980) turned “Armani” into a household name. Hollywood stars like Julia Roberts and Michelle Pfeiffer were soon gliding down red carpets in his creations, and Pat Riley began sporting his suits while coaching the Knicks. (I think I speak for all Knicks fans when I say that no coach could’ve looked better than he did when he blew the title for us in ’94. Sports grudges die hard.)

Armani’s empire grew with the precision of his tailoring. By 2001, he was hailed as Italy’s most successful designer. His collaborations — fragrances with L’Oréal, costumes for films like The Untouchables — cemented his cultural reach. Yet Armani remained fiercely independent, resisting the conglomerates that swallowed other houses. He was “Re Giorgio” — King Giorgio — a nickname that stuck because he ruled his domain with absolute clarity of vision.

What set Armani apart was his philosophy: elegance wasn’t about ostentation but about being remembered. His clothes didn’t shout; they whispered, leaving an impression that lingered like a well-placed brushstroke. He revolutionized menswear by introducing the “greige” palette — those subtle, not-quite-grey shades that became his signature — and paired fitted T-shirts with unstructured jackets, creating a casual chic that felt revolutionary. In Italy, where men’s fashion once meant stiff suits, Armani offered liberation without sacrificing style. His influence rippled globally, shaping how the world dressed for boardrooms and beyond. His minimalist aesthetic became a cultural shorthand for power and poise, influencing designers from New York to Tokyo. Armani’s vision of relaxed luxury reshaped corporate wardrobes, red-carpet glamour, and even streetwear, inspiring a generation of labels to prioritize simplicity over spectacle. His impact endures in the global obsession with “quiet luxury,” a term that might as well have been coined for him.

Even as he approached his 90s, Armani never slowed. He was at his desk until his final days, sketching collections and planning his brand’s 50th anniversary. His absence from recent shows raised eyebrows, but Armani’s focus remained on the work, not the spotlight. He wasn’t just a designer; he was a cultural force, dressing the powerful and redefining power itself. His legacy is woven into every tailored jacket, every red-carpet gown, every moment where style feels effortless because Armani made it so.

In Italy, Giorgio Armani will always be a national treasure, a symbol of Made in Italy excellence. Globally, his legacy is one of realized imagination: of a man who saw the world not as it was but as it could be—sharper, sleeker, and effortlessly elegant. As he once told Esquire, “Perfection in style, for me, is when you don’t notice the effort, only the result.” That was Giorgio Armani: the effort is invisible, but the result is unforgettable.

Daniel Ross Goodman is a Washington Examiner contributing writer and the Allen and Joan Bildner Visiting Scholar at Rutgers University. His next book, Dante’s Guide to Life: How The Divine Comedy Can Change Our Fortunes, Our World, and Ourselves, will be published in 2026 by Angelico Press.