You may remember the stories about how college students, even English Lit ones, had lost the ability to read novels.

Nicholas Dames has taught Literature Humanities, Columbia University’s required great-books course, since 1998. He loves the job, but it has changed. Over the past decade, students have become overwhelmed by the reading. College kids have never read everything they’re assigned, of course, but this feels different. Dames’s students now seem bewildered by the thought of finishing multiple books a semester. His colleagues have noticed the same problem. Many students no longer arrive at college—even at highly selective, elite colleges—prepared to read books.

This development puzzled Dames until one day during the fall 2022 semester, when a first-year student came to his office hours to share how challenging she had found the early assignments. Lit Hum often requires students to read a book, sometimes a very long and dense one, in just a week or two. But the student told Dames that, at her public high school, she had never been required to read an entire book. She had been assigned excerpts, poetry, and news articles, but not a single book cover to cover.

“My jaw dropped,” Dames told me. The anecdote helped explain the change he was seeing in his students: It’s not that they don’t want to do the reading. It’s that they don’t know how. Middle and high schools have stopped asking them to.

Faced with this predicament, many college professors feel they have no choice but to assign less reading and lower their expectations. Victoria Kahn, who has taught literature at UC Berkeley since 1997, used to assign 200 pages each week. Now she assigns less than half of that. “I don’t do the whole Iliad. I assign books of The Iliad. I hope that some of them will read the whole thing,” Kahn told me. “It’s not like I can say, ‘Okay, over the next three weeks, I expect you to read The Iliad,’ because they’re not going to do it.”

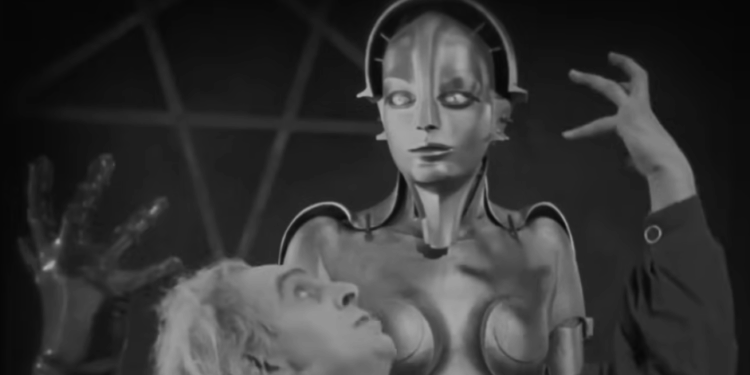

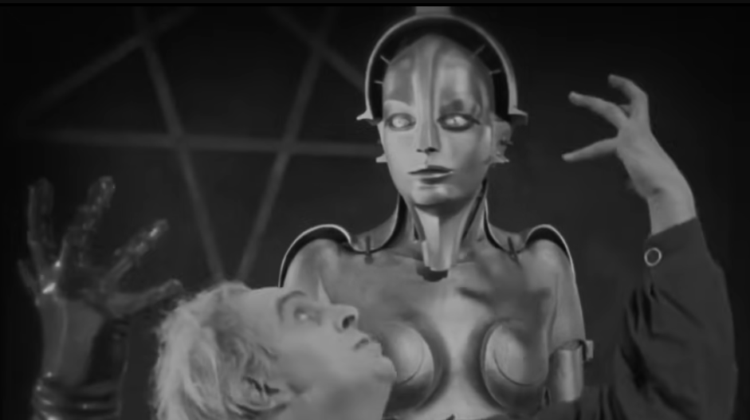

Can they watch movies? No, and while this is more about the study of film, film audiences are aging and it’s not just that Gen Z is less likely to go to theaters, they’re less capable of watching a conventional ‘film’ as opposed to the 300,000 spliced together fight scenes, close ups, special effects shots overlaid with ironic music choices and quips that make up a Marvel movie and have no coherent plot.

They watch podcasts and clips of things. Not movies.

Everyone knows it’s hard to get college students to do the reading—remember books? But the attention-span crisis is not limited to the written word. Professors are now finding that they can’t even get film students—film students—to sit through movies. “I used to think, If homework is watching a movie, that is the best homework ever,” Craig Erpelding, a film professor at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, told me. “But students will not do it.”

I heard similar observations from 20 film-studies professors around the country. They told me that over the past decade, and particularly since the pandemic, students have struggled to pay attention to feature-length films. Malcolm Turvey, the founding director of Tufts University’s Film and Media Studies Program, officially bans electronics during film screenings. Enforcing the ban is another matter: About half the class ends up looking furtively at their phones.

Akira Mizuta Lippit, a cinema and media-studies professor at the University of Southern California—home to perhaps the top film program in the country—said that his students remind him of nicotine addicts going through withdrawal during screenings: The longer they go without checking their phone, the more they fidget. Eventually, they give in. He recently screened the 1974 Francis Ford Coppola classic The Conversation. At the outset, he told students that even if they ignored parts of the film, they needed to watch the famously essential and prophetic final scene. Even that request proved too much for some of the class. When the scene played, Lippit noticed that several students were staring at their phones, he told me. “You do have to just pay attention at the very end, and I just can’t get everybody to do that,” he said.

Many students are resisting the idea of in-person screenings altogether. Given the ease of streaming assignments from their dorm rooms, they see gathering in a campus theater as an imposition. Professors whose syllabi require in-person screenings outside of class time might see their enrollment drop, Meredith Ward, director of the Program in Film and Media Studies at Johns Hopkins University, told me. Accordingly, many professors now allow students to stream movies on their own time.

You can imagine how that turns out. At Indiana University, where Erpelding worked until 2024, professors could track whether students watched films on the campus’s internal streaming platform. Fewer than 50 percent would even start the movies, he said, and only about 20 percent made it to the end. (Recall that these are students who chose to take a film class.)

After watching movies distractedly—if they watch them at all—students unsurprisingly can’t answer basic questions about what they saw. In a multiple-choice question on a recent final exam, Jeff Smith, a film professor at UW Madison, asked what happens at the end of the Truffaut film Jules and Jim. More than half of the class picked one of the wrong options, saying that characters hide from the Nazis (the film takes place during World War I) or get drunk with Ernest Hemingway (who does not appear in the movie). Smith has administered similar exams for almost two decades; he had to grade his most recent exam on a curve to keep students’ marks within a normal range.

Everyone grades them on a curve. And that’s the problem.

Matt Damon, the star of many movies that college students may not have seen, said that Netflix has started encouraging filmmakers to put action sequences in the first five minutes of a film to get viewers hooked. And just because young people are streaming movies, it doesn’t mean they’re paying attention. When they sit down to watch, many are browsing social media on a second screen. Netflix has accordingly advised directors to have characters repeat the plot three or four times so that multitasking audiences can keep up with what’s happening, Damon said.

Believe it or not, movies are joining novels as a niche art. The future will be some sort of interactive videogame that can be watched distractedly or interacted with in bite size segments. Movies, like novels, will be for a smaller and more discerning audience.