If the U.S. Navy is to retain its status as the premier fleet in the world, we must address the issue that our shipyards are failing.

The U.S. Government Accountability Office has reported that Navy shipbuilding programs have routinely exceeded their budgets and schedules. For instance, the Zumwalt-class destroyer program experienced a total cost of $24.5 billion for three ships, averaging about $8 billion per ship, which was significantly higher than initial estimates.

A 2024 GAO report indicated that the Navy’s ship design practices often lack alignment with leading commercial practices. This misalignment contributes to delays and cost overruns, as projects proceed without a full understanding of design maturity and readiness for construction.

The GAO has also identified that U.S. shipyards face significant workforce shortages and aging infrastructure. These issues hinder the ability to meet the Navy’s shipbuilding goals, with fewer than 40% of ships completing repairs on time, even when space is available in shipyards.

Since 2015, the GAO has made 90 recommendations to the Navy to improve shipbuilding practices. However, as with recent reports, 60 of these recommendations remain unaddressed, indicating a lack of comprehensive action to resolve persistent issues.

Although maritime threats have been growing, the Navy has not increased its fleet size as planned over the past 20 years. Over this period, GAO has found that the Navy’s shipbuilding acquisition practices consistently resulted in cost growth, delivery delays, and ships that do not perform as expected. For example, GAO identified schedule risks in 2024 for the Constellation class frigate program. Counter to leading ship design practices, construction for the lead ship started before the ship design work was complete, and delivery is expected to be delayed by at least 3 years.

The Navy’s recent practices with the frigate program are similar to its prior performance with its Littoral Combat Ship and Zumwalt Class Destroyer programs. Both programs were hampered by weak business cases that over-promised the capability that the Navy could deliver. Together, these two ship classes consumed tens of billions of dollars more to acquire than initially budgeted and ultimately delivered far less capability and capacity to fleet users than the Navy had promised. The Navy cannot expect to look within its existing playbook to find answers. Current challenges can provide the Navy leadership with the impetus to look for solutions outside of the existing defense acquisition paradigm. Specifically, the Navy can innovate by using effective, proven ship design practices and product development approaches that are rooted in the approaches of industry-leading companies worldwide.

GAO has previously identified leading ship design practices used by commercial ship buyers and builders that the Navy can use to achieve more timely, predictable outcomes for its shipbuilding programs.

While the U.S. Navy struggles to maintain readiness, we face a growing threat from China. The Chinese are building hundreds of ships for both their navy and coast guard.

Added to this is their Maritime Militia, which consists of thousands of smaller craft. Against this, the Navy currently has 50-70 ships in the 7th Fleet, not all of them forward in the vicinity of China.

So, let’s see how this sets up. We have 50-70 ships in the Pacific Fleet, many as far back as San Diego and Seattle area, and it takes weeks of just sailing time, not to mention the time it takes to sortie and actually get to sea. Meanwhile, the Chinese already have 695 ships in theater to do whatever they want — to either attack our enemies or establish a blockade (of Taiwan, for example) or interfere with commerce.

According to the Commander, USINDOPACOM, Adm. Paparo, “China’s accelerated shipbuilding capabilities is producing naval combatants at a rate of approximately 6 to every 1.8 that the U.S. builds, nearly tripling the U.S. output. This disparity underscores the growing challenge in maintaining maritime dominance in the Indo-Pacific region.”

How long will it take the Navy to get to the fight in the Pacific? What is the tyranny of distance? Most people think that the world of 2025 has shrunk. One can hop on a plane and be anywhere in the world within hours. That kind of thinking excludes the reality of travel times by sea. Realistically, it will take the Navy weeks, if not months, to deploy forward to the Pacific when the need arises. Without enough ships forward, the potential for the PRC to quickly overwhelm our forces in the area and invade Taiwan (which is their number one military priority) before we can have more ships in the area to oppose them is overwhelming.

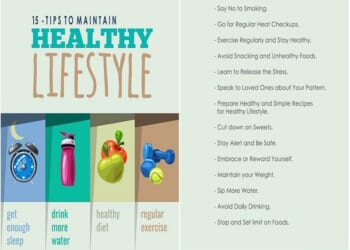

Why do we need combat ships? Aside from the obvious need to be able to fight and win wars at sea, the Navy needs to keep the sea lanes open even while fighting a war for commerce not just in the Pacific but all over the world. Here is a summary of essential commodities that must travel by sea:

- Rare earth elements used in military technology, such as missiles, jet engines, EVs, wind turbines, electronics, and radars

- Critical minerals such as cobalt, lithium, graphite, titanium, nickel, and manganese, most of which come from Africa, South America, and Australia

- Energy materials, including crude oil, liquefied natural gas, and uranium.

- Industrial and strategic chemicals such as ammonia, aluminum oxide (bauxite), and chlorine-based compounds

- Finished and semi-finished industrial products such as ball bearings, specialty alloys, and advanced electronic components from Germany, Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea

Other factors to consider about the need for open shipping lanes that require our Navy on the scene all over the world include:

- 90% of world trade travels by sea, including most strategic materials.

- Many materials pass through vulnerable chokepoints like the Strait of Hormuz, the Suez Canal, and the South China Sea.

- The U.S. lacks sufficient domestic production or refinement capacity for several of these items, making sea lanes vital to economic and military readiness.

Our defense and economy depend on raw materials that travel by sea.