Order Michael Finch’s new book, A Time to Stand: HERE. Prof. Jason Hill calls it “an aesthetic and political tour de force.”

Sign up to attend Michael’s talk in Los Angeles on Thursday, November 20: HERE.

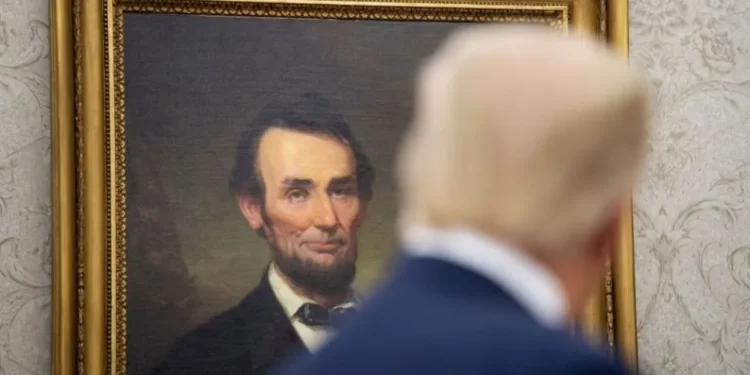

Abraham Lincoln, as is generally known, preserved the Union, and with it, he also preserved both constitutional rule and, as he had pointed out so eloquently, the very idea of representative government. Yet it is widely forgotten today that in acting to do this, Lincoln took some actions that led him, like Donald Trump today, to Democrats charging him with being a tyrant and a dictator in the making.

As Rating America’s Presidents shows, some of Lincoln’s critics claimed, both then and now, that some of Lincoln’s measures to keep the United States together involved his trampling upon the Constitution and behaving like a despot. Like Trump, Lincoln insisted that his actions were entirely legal, but suspicions and bitterness lingered in some quarters. This claim about Lincoln rests primarily upon Lincoln’s April 1861 suspension of habeas corpus, the right of a defendant to be brought before a judge or court rather than simply held indefinitely.

Lincoln knew that if Maryland, a slave state, left the Union and Washington, D.C., became surrounded by hostile territory, with Maryland to the north and Virginia to the south, the war would be lost and secession accomplished. Accordingly, when angry mobs attacked federal troop transports in Baltimore and the state of Maryland asked Lincoln to remove Union troops from its territory, Lincoln ordered the suspension of habeas corpus in the areas of Maryland where the fervor to join the Confederacy was strongest.

Lincoln argued that he was exercising his lawful Constitutional authority as president of the United States. The Constitution gave Congress the authority to suspend habeas corpus “in cases of Rebellion or Invasion,” but Congress was not in session at the time. Lincoln justified his action by arguing that time was of the essence, and only the president could act quickly, in his role as commander in chief of the armed forces, to preserve the Union in this time of large-scale insurrection.

Lincoln had not seized powers that were not in the Constitution; he had assumed, in a time of crisis, powers that the Constitution delegated to Congress. Congress later ratified his actions. That he had no intention of becoming the dictator and tyrant that his detractors accused him of being was clear from the many things he did not do that characterize the behavior of real dictators: he did not suspend habeas corpus indefinitely or universally; he did not profit personally from his actions; he did not issue a sweeping decree abolishing slavery in the Union, but instead asked Congress for a constitutional amendment that would phase slavery out extremely gradually, ending with the institution’s extinction in 1900.

In addition, Lincoln did not suspend the free press, which was often harshly critical of his actions, and he did not arrest his political opponents or suspend the 1864 presidential election (which, at one point, he was quite sure he would lose). He never even considered such measures. He did set a precedent for the growth of the power of the executive branch, but this precedent should never have been followed without a repetition of the conditions that led Lincoln to take the course he chose: a civil war.

Critics also excoriated Lincoln for not asking Congress for a declaration of war before going to war with the Confederacy. But a centerpiece of his approach to the South was a refusal to accord it the recognition that belligerent states usually gave to their enemies; to do so would, he argued, be a tacit admission that the South was indeed an independent nation, which was the very claim he was going to war to contradict.

The South, Lincoln said, was a region of the United States in rebellion against lawful authority. The Constitution did not require a declaration of war to put down an insurrection. Abraham Lincoln was forced to articulate and defend the reasons for going to war and continuing the war after staggering losses on both sides; with his remarkable skills as a rhetorician, he articulated not only a justification for the war, but for representative government itself.

In doing so, he was the first president to become the nation’s spokesman, conscience, and philosophical guide. Many of his successors would attempt to emulate him, with varying degrees of success.