“Made in China” has long been the most common manufacturing mark on goods Americans buy, especially so if those goods are inexpensive. From little, kitschy trinkets to watches, clothing, computers, and cellphones, nearly any kind of product out there has likely been made in China.

The reason for this, of course, is that manufacturing in China is significantly cheaper than doing so in the U.S. Americans like buying cheap products because we are a consumeristic society that is addicted to new stuff.

In many cases, the quality and durability of a product are secondary to its cost. And since “Made in China” usually means cheaper, accepting that the product is of lesser quality is a given.

Furthermore, Americans and much of the Western world have viewed China’s economic prowess primarily through the lens of its role as a mass manufacturing hub. China may excel at manufacturing a wide range of products, but technological innovation is dominated mainly by the West, particularly the U.S.

This has been the case for decades, but that paradigm may be shifting, and rapidly so.

Following a recent trip to China, Ford CEO Jim Farley called it “the most humbling thing I’ve ever seen.” He had toured a number of China’s automobile factories and was blown away by what he saw. “Their cost, the quality of their vehicles, is far superior to what I see in the West,” he stated. “We are in a global competition with China, and it’s not just EVs.” Farley warned, “And if we lose this, we do not have a future at Ford.”

Yikes.

Farley is not the only Western manufacturer ringing alarm bells. Several others from both the U.S. and Europe have noted a shift not only in the improving quality of Chinese goods, especially tech goods, but also in its means of production.

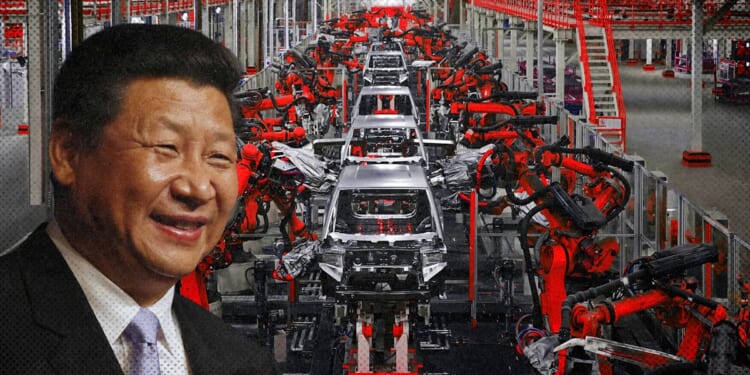

The image of China being awash in sweatshops with hundreds of employees working long hours, churning out products at near slave wages, is becoming a thing of the past.

China is embracing the robot manufacturing revolution faster than any other nation. Increasingly, Chinese factories are becoming filled with robots. Over the last decade, China has grown its industrial robot count from 189,000 in 2014 to more than two million by 2024. And the pace is only increasing as China added 295,000 robots last year alone. By comparison, the U.S. added just 34,000 robots last year.

China also has the highest robots-to-manufacturing-worker ratio, with 567 robots per 10,000 workers. In the U.S., the ratio is 307 robots per 10,000 workers.

China’s robot revolution has enabled workers to shift from lower-skilled tasks to higher-skilled jobs. According to Greg Jackson, the head of the British energy company Octopus, “China’s competitiveness has gone from being about government subsidies and low wages to a tremendous number of highly skilled, educated engineers who are innovating like mad.”

With products like electric vehicles, China is outpacing the competition not merely in numbers and lower costs, but in its innovative technologies.

From a geopolitical perspective, Beijing’s efforts to effectively corner the market on rare earth minerals, combined with China’s growing innovation, make its threat that much more dangerous.

The last thing China wants is for the West to catch up. These rare earth minerals are a national security interest to the U.S., as they are essential for manufacturing various electronic components, particularly those used in chip-making for smart weaponry.

With China now accounting for 70% of rare earth mining and 90% of refining, Beijing has found a new way to flex its economic muscles. While the U.S. still leads China in AI chip development, Beijing is attempting to strong-arm the Trump administration into easing up its restrictions on exporting these chips and other tech to China.

As a result, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent recently stated that, due to Beijing pointing “a bazooka at the supply chains and the industrial base of the entire free world,” the Trump administration and our European allies are collaborating to address this threat. As Bessent further warned, “If China wants to be an unreliable partner to the world, then the world will have to decouple” from China.

That is a prospect that is much more easily said than done. It is the right attitude, but the question is, does Beijing already have too strong an upper hand?