William McKinley arrived in St. Louis for the 1896 Republican National Convention with eyes on the presidency and the support of Marcus Hanna, the influential “kingmaker,” but no assurance that his nomination would occur. But occur it did when he secured the nomination on the first ballot, defeating House Speaker Thomas Reed 661 to 84 votes. That’s a ringing endorsement from a political party determined to win back the White House and move the nation forward toward the 20th century.

The Democrats met in Chicago and nominated William Jennings Bryan — an orator, evangelical leader, veteran of the House of Representatives, and mighty force in the party who campaigned on a federal income tax, statehood for Western states (Arizona, New Mexico, and Oklahoma), free silver and an end to the gold standard, and no protective tariffs, among other issues.

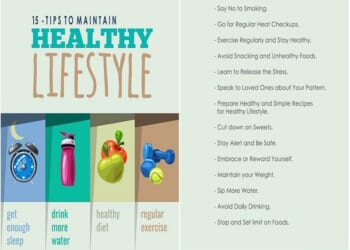

McKinley responded with a push to build a canal across Central America, expand the U.S. Navy, pay women equally for equal work (surprising for 1896, right?), create an arbitration board to end crippling strikes, and acquire Hawaii. These platform issues and others were distributed to voters across the nation via a mass printing of almost 200 million pamphlets and a series of 350 speeches shared through the print media. His Republican Party Speakers Bureau spread out across the nation, sharing his message and finding fault with Bryan’s ideas.

When Election Day arrived and the ballots were counted, McKinley handily defeated Bryan, known by his followers as “The Commoner,” by more than 600,000 votes. The Republican Party had successfully built a coalition of urban residents, industrial workers, successful farmers, reformers, and the larger ethnic groups, excluding the Irish, who remained solidly Democrat.

Domestic and foreign policy issues awaited McKinley’s leadership, and he stepped forward while being hesitant to alienate voters too often.

While the gold standard vs. bimetallism debate consumed much of his early days, when the major European nations hesitated to move to gold and silver, the president threw his support to the gold standard and in 1900 signed legislation placing U.S. money on the gold standard.

In the area of race relations, McKinley hesitated to enrage the South by pushing for voter rights or support legislation and governmental practices against violence toward black Americans. He appointed less than 50 black Americans to posts within the government, but in reality, the positions lacked power and were often considered “window dressing.” While he did address the issue of lynchings, he never ordered government forces to engage in a legal fight to stop the practice or prosecute the offenders.

The president worked to increase organized labor’s role in the economy by supporting the Dingley Tariff, working alongside labor leaders such as Samuel Gompers and supporting limitations on Chinese immigrant workers. By increasing tariffs, he could reduce internal taxes and at the same time push for the creation of new jobs for U.S. workers.

The last quarter of the 19th century witnessed a second great wave of colonization, and the international conversation seemed to focus on “greatness” as defined by increasing spheres of influence. Those increasing spheres of influence required a powerful navy, an organized merchant marine force, protectorates over “weaker” nations, and rhetoric that justified expansionist policies. The debate was heated in the United States, with recognizable figures like Mark Twain and Andrew Carnegie criticizing the accumulation of overseas colonies, earning the label of anti-imperialists. (For a good refresher course on imperialism, grab a copy of Rudyard Kipling’s “The White Man’s Burden.”)

As the nation was attempting to navigate imperialism and numerous other potential political landmines, Cuba erupted in revolution. Cubans demanded independence from Spain, and Spain retaliated with brutal force, including the use of corralled incarceration camps. The United States government struggled with its reaction; many individual citizens sided with the rebels, while those with large economic investments in Cuba feared a major financial loss. The attempts to negotiate a peace continued with little resolution.

When McKinley sent the USS Maine to Havana to “protect U.S. citizens and property” and the Spanish government responded by ridiculing the “weak” U.S. president, popular opinion turned against Spain. The explosion that resulted in the sinking of the Maine propelled the U.S. into war that lasted only four months and resulted in a victory that witnessed the United States gain Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippine Islands (small price tag of $20 million). Cuba became a U.S. protectorate (there’s that word again!) through a treaty approved by the Senate by only a one-vote margin.

McKinley had marched the United States into a new role — colonial power.

What was next?