“The Muslim Brotherhood,” the late historian Barry Rubin once remarked, “is by far the most successful Islamist group in the world.” But nearly a century after its creation, and decades after it spawned dozens of terrorist organizations, the Brotherhood isn’t designated as a terrorist group by the United States. Now, some in the U.S. Congress are trying to change that.

On June 10, 2025, Rep. Nancy Mace (R-SC) introduced legislation to designate the Muslim Brotherhood as a foreign terrorist organization, or FTO. The Muslim Brotherhood Is a Terrorist Organization Act calls for the secretary of state to list the group as an FTO under Section 219 of the Immigration and Nationality Act. Mace’s office said the legislation would enable financial sanctions, asset freezes, travel bans, and targeted law enforcement to “dismantle the group’s operations in the U.S. and abroad.”

“The Muslim Brotherhood doesn’t just support terrorism; it inspires it,” Mace said in a press release. The group “is a threat to global security, and it’s long past time we call them what they are: terrorists.”

In the upper chamber, Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX) expressed his support. Cruz told the Hill that “the Muslim Brotherhood uses political violence to achieve political ends and destabilize American allies, both within countries and across national boundaries.”

The senator also noted the danger the group poses: “The Palestinian branch of the Muslim Brotherhood is Hamas, a terrorist group which on Oct. 7 committed the largest one-day massacre of Jews since the Holocaust, and which included the murder and kidnapping of dozens of Americans.” Such bluntness is unfortunately rare when it comes to discussing the group.

Indeed, there’s no question that the Brotherhood inspires violence, including on American soil. On June 1, 2025, Mohamed Sabry Soliman threw Molotov cocktails at a pro-Israel gathering in Boulder, Colorado. Fifteen people, many of them elderly and at least one a Holocaust survivor, were injured. One, an 82-year-old woman, later died. Eight decades after the Holocaust, Jews were being burned alive far from the shores of the Middle East. According to the FBI, Soliman, an illegal immigrant from Egypt, had planned the attack for months. Soliman shouted “Free Palestine” while allegedly committing the attack, and he told investigators that he was driven by a desire to “kill all Zionist people.” Soliman reportedly admitted that “he had been planning the attack for a year and was waiting until after his daughter graduated to conduct the attack.” According to CNN, Soliman had expressed his support for the Brotherhood on social media.

Notably, Cruz’s support for designating the Brotherhood isn’t new. The senator has introduced similar legislation on several occasions, most recently in 2021 when he noted that “we have a duty to hold the Muslim Brotherhood accountable for their role in financing and promoting terrorism across the Middle East.” There have been other efforts throughout the years. In his first term, President Donald Trump expressed support for the idea. Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el Sisi reportedly encouraged the designation in an April 2019 meeting with then-White House press secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders, who said: “The president has consulted with his national security team and leaders in the region who share his concern, and this designation is working its way through the internal process.”

But thus far, the Brotherhood has avoided this fate, partly thanks to claims that it doesn’t neatly fit the definition of an FTO. As Jonathan Schanzer, the executive director for the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank, noted, “Such efforts petered out.” Indeed, previous attempts to apply the designation to the group have been met with criticism.

In 2019, the New York Times firmly asserted that the Muslim Brotherhood couldn’t be considered a terrorist group. And the Washington Post painted such efforts as “right wing,” saying that “almost all academics and analysts, even those critical of the Brotherhood, agree that it is not a terrorist organization.” For good measure, the newspaper claimed that “such a designation would introduce a plethora of political problems in the Middle East and at home.”

Other critics present an FTO designation as unworkable. The Brotherhood, they argue, is loosely knit, more of a group of disparate thinkers than a terrorist organization. And you can’t, they claim, kill an idea, much less a group of philosophers, however abhorrent their philosophies. None of this is true. Fully killing an idea is difficult, but you can, at least, put it on life support, as the Allied war against fascism and Japanese militarism demonstrated. Further, the Brotherhood itself is not amorphous. In fact, membership in the group is difficult to obtain and tightly controlled. The Brotherhood is organized. That organization and rigidity are what enabled the Brotherhood briefly to win, and subsequently lose, power in Egypt a decade and a half ago. Its rise and fall were a long time coming.

Indeed, there are good reasons to explore an FTO designation. In many respects, it is the Muslim Brotherhood that birthed the modern age of terrorism. And a look at the organization’s history, as well as its ideology, leaves little doubt as to its intentions.

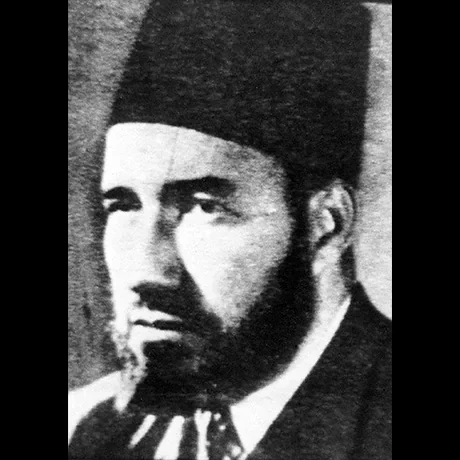

The Muslim Brotherhood was born in Ismailia, Egypt, in 1928, fathered by an errant and charismatic schoolteacher named Hassan al Banna, who was then a mere 21 years of age. In his memoirs, al Banna claimed that six men came to see him, swearing their allegiance. “We are all sick of this life: a life of shame and shackles,” they allegedly said. “Here you see that the Muslim Arabs have no chance of status or respect in this country. … We do not see the way to work as you see it or know the path to serve the country and the religion as you do. All we want now is to offer to you what we possess so that we are exonerated in front of God. You are in charge of it and what we do.” The Society of the Muslim Brothers, also known as al Ikhwan al Muslimin, or the Ikhwan, was a product of its place and time, but its beliefs would resonate to the present day. The group’s reliance on myth and mysticism, evident in its founding story, would also endure.

Egypt in the 1920s was, in many respects, a crippled nation. The British had occupied the country for half a century. Egypt had nominally been under the Ottoman Empire. However, the British had effectively controlled the country since 1882 and the aftermath of the Urabi revolt, which aimed to oust foreign influence. The British sought to preserve access to the Suez Canal and, with it, trade with their “crown jewel,” India. An entire generation of British officers cut their teeth in Egypt, with a number of them, perhaps most notably Horatio Herbert Kitchener, the future secretary of state for war, exerting great influence in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. For many Westerners, Egypt was all “hustle and bustle,” as a young British subaltern named Winston Churchill, who would fight in wars on its periphery, remarked in 1898.

The Allied victory in World War I put an end to the Ottoman Empire, long labeled the “sick man of Europe.” The empire had long been desultory. One British visitor, Gertrude Bell, had said: “No country which turned to the eye of the world an appearance of established rule and centralized Government was, to a greater extent than the Ottoman Empire, a land of make-believe.” On the eve of World War I, a mere 5% of taxes were collected by the government, a government that not only failed to collect taxes but was heavily in debt to foreign powers, many of which had cordoned off spheres of influence, even stationing military bases, training police forces, and building their own universities and corporations. In many respects, the empire was but a collection of tribes. The coming fall would give them flags and set about a period of infighting.

With the Ottomans’ collapse, British and French influence expanded through the Middle East. For many of the region’s Muslims, even those Arabs who were glad to be rid of their Ottoman Turkish overlords, rule by non-Muslims was not only intolerable but also unthinkable. Outcry against foreign rule grew, with revolts erupting in British-ruled Iraq and French-controlled Syria, and elsewhere. In March 1924, the Ottoman Caliphate, which had been the center of Muslim religious life for years, was abolished. Previously, “religion,” the late historian David Fromkin noted, “had some sort of unifying effect, for the empire was a theocracy — a Muslim rather than a Turkish state — and most of its subjects were Muslims.” But now, unity seemed to be a distant idea. For many denizens of the former Ottoman Empire, things came apart.

The end of Ottoman rule and the abolition of the caliphate left many Muslims in the once great empire feeling adrift. As the historian Martyn Frampton noted in his 2018 history of the Brotherhood, it was “a world upside down.” A sense of resentment had been kindled, fed by the ashes of a lost empire, a vanishing sense of greatness, and foreign occupation. There was a desire to look back to a golden era, even if it was largely imagined, while casting about for a new future. The Brotherhood offered answers and promised solutions.

By 1928, Egypt had marked six years of nominal independence. But the British remained, and so too did a sense of decay, decrepitude, and loss. And the Brotherhood, with its talk of a spiritual and political rebirth, was on to something. At its core, it was a revivalist movement. But the reformers were Islamists.

Al Banna and his acolytes argued that the once-great Muslim empire had collapsed, and the non-Muslim West had emerged triumphant, because Muslims and their rulers were corrupt and had lost their way. To al Banna and his followers, redemption would only come from a strict adherence to their interpretation of the teachings of the Prophet Muhammad. The logic was hardly original: A group of thinkers known as Salafists had been making similar arguments for centuries. But circumstances had conspired to give al Banna’s reasoning popular appeal.

The Ottoman Empire had once been home to many non-Muslim minorities. Indeed, at one point, no less than a third of Baghdad was Jewish. Beginning in the 1830s, efforts to reform and revitalize the empire had helped spark growing intolerance. Increasingly, many non-Muslims, known as dhimmis, found themselves persecuted, both officially and unofficially — a trajectory that culminated in increasing violence against Christians and Jews and several massacres of Armenians, Maronites, and Jews, among others.

The Brotherhood preached bigotry and subservience to its beliefs. And the future, its members were certain, was theirs. Presaging Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, Osama bin Laden, and others, al Banna argued that the West “is now bankrupt and in decline … its foundations are crumbling.” The key to “national greatness” could only be found with his militant brand of Islam, which must be, he was sure, all-encompassing. Fanaticism was not only a virtue but essential to rebirthing a once great civilization. Like other forms of 20th-century authoritarianism, it foresaw a utopian future, albeit one built on violence and subjugation.

Al Banna soon garnered quite a following, and the Brotherhood issued a series of publications and propaganda and even established its own press. Initially, the Brotherhood focused on recruitment and social welfare programs, rapidly boosting its membership — and heralding the threat it would pose to Egyptian rulers who would alternately fete and imprison their erstwhile rivals for power. World War II and the 1948 recreation of Israel resulted in this tenuous truce coming apart. Al Banna raised funds and arms and sent warriors in a jihad to destroy the fledgling Jewish state. The growing threat that he posed to the Egyptian government of King Farouk led to al Banna’s assassination in 1949. Upon his death, the New York Times wrote: “Sheikh Hasan’s followers were fanatically devoted to him, and many of them proclaimed that he alone would be able to save the Arab and Islamic worlds.” Al Banna was dead, but his ideas would live on.

Farouk, an overweight playboy with little taste for ruling, was deposed. His effective successor, Gamal Abdel Nasser, a young military colonel, was an altogether different character. Nasser recognized the Brotherhood as a threat to his rule. While he wasn’t adverse to appeasing the group when necessary, Nasser waged war on it, imprisoning and assassinating top officials and forcing many to go underground — or abroad.

In the wake of the crackdown, many Muslim Brothers fled, both to elsewhere in the Middle East — Saudi Arabia, the chief rival of Nasser’s Egypt, was a favorite destination — and to the West. This era also coincided with the dawn of the Cold War. Some in the U.S., notably CIA officials, thought that the Brotherhood would have a role to play against the atheist Soviet Union.

As the journalist Ian Johnson documented in his 2010 book A Mosque in Munich, the agency viewed the Brotherhood and political Islam as tools to be weaponized against Soviet influence. The idea was hardly original. Both the Nazis and Imperial Germany had tried to harness radical Islam to their own ends. The net result, Johnson noted, was that the CIA funded a variety of Brotherhood-linked groups, mosques, radio stations, and publications — with portentous results for the future.

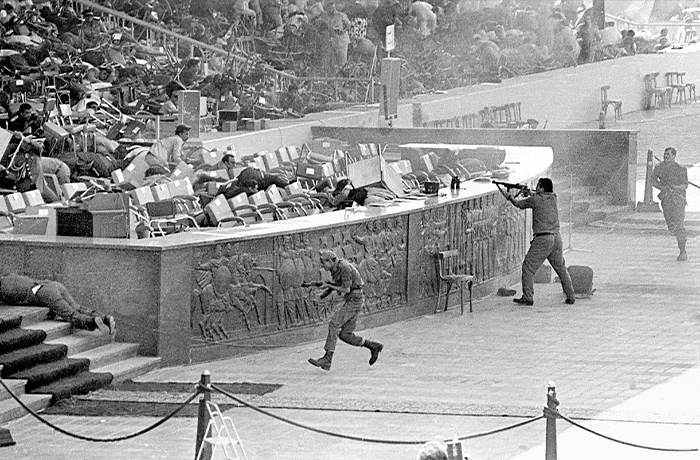

The Brotherhood’s ideas, enabled by a naïve West and nurtured by a wellspring of resentment in the Middle East, continued to gain converts. Nasser’s successor, Anwar Sadat, attempted a détente with the group. But Sadat’s decision to make peace with Israel led to the Egyptian leader’s assassination by jihadists in 1981.

One of the jihadists who was subsequently imprisoned, an Egyptian doctor named Ayman al Zawahiri, had joined the Brotherhood in the 1960s. He would later gain infamy as bin Laden’s second-in-command and the eventual leader of al Qaeda. The Brotherhood had radicalized the young man who had been born into a prominent family. His war against the West and nonbelievers would stretch for more than half a century, only ending with a U.S. strike in Afghanistan in 2022. Bin Laden himself was a member of the Brotherhood. “We were hoping to establish an Islamic state anywhere,” his friend Jamal Khashoggi, a future Washington Post columnist, once told the journalist Lawrence Wright. “We believed that the first one would lead to another, and that would have a domino effect which could reverse the history of mankind.” Khashoggi, Wright notes, joined the Brotherhood “at about the same time” as bin Laden.

The Muslim Brotherhood is the fountainhead of jihad.

This, perhaps, is the Brotherhood’s great legacy: Its ideas have germinated across borders and cultures. And, like a deadly virus, they contaminate their host, spreading death and destruction. The group’s unrepentant antisemitism has extended far from Egyptian soil. In his lifetime, al Banna, a schoolteacher, had been a big believer in the power of education. Commensurately, the Brotherhood has used schools and universities, including in the West, to push its ideology. The antisemitism that has exploded across college campuses, nurtured by anti-American and anti-Israel groups, didn’t appear from nowhere.

Several countries, including Middle Eastern nations like Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates, have recognized the dangers posed by the Brotherhood, designating the group as an FTO. In April 2025, the Kingdom of Jordan, long coveted by the Brotherhood, did likewise. Whether the U.S. will do the same remains to be seen. But the fact that the Brotherhood poses a threat can’t be doubted. Its history says as much.

Sean Durns is a senior research analyst for CAMERA, the 65,000-member, Boston-based Committee for Accuracy in Middle East Reporting and Analysis.