Some brands become so dominant in their function that their names eclipse generic terms. We ask for a Kleenex instead of a tissue or Google a topic instead of searching the internet. When the word “Pinkertons” is uttered, we conjure the same image: a private detective, or at least hired muscle. That name, Pinkerton, has become more than a man in the American ethos. It’s shorthand for an entire industry that still exists today.

“Pinkerton made his mark not only in his own time but also on posterity,” writes Rhodri Jeffreys-Jones in Allan Pinkerton: America’s Legendary Detective and the Birth of Private Security. “The management of his renowned firm, the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, passed on his death to his sons. The resultant dynasty lasted until the passing of the last of his direct male descendants in 1967. Even after that and despite several mergers, the Pinkertons remained a force on the land.”

Throughout the first half of the book, Jeffreys-Jones peels back the layers of legend to reveal the man, his agency, and the long shadow they cast over American culture. Using what he can find — much of the firsthand documentation from the agency was lost in a fire — the author tells a sweeping story that challenges the official record. It is equally clear, however, that Jeffreys-Jones is determined to knock his subject down a peg.

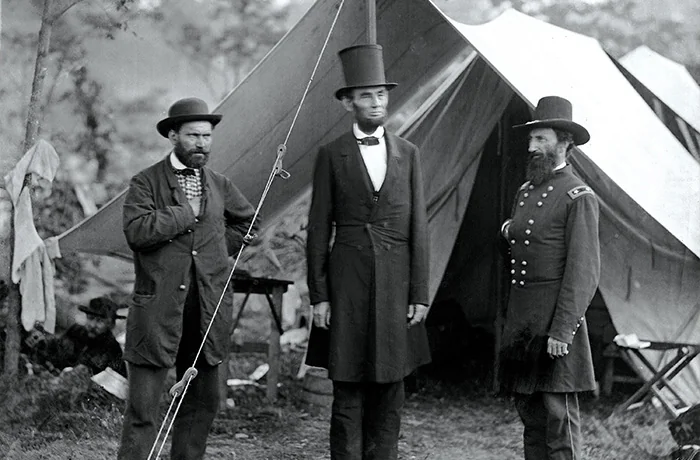

Allan Pinkerton’s rise from a Scottish immigrant to America’s first celebrity detective, who rubbed shoulders with the rich and powerful, truly fits the archetype of the American dream. After fleeing to the United States following his participation in the revolutionary Chartist movement back home, where the author eagerly speculates he may have informed on fellow activists, Pinkerton capitalized on the lawless edges of a rapidly expanding republic. He helped pioneer modern investigative techniques, most notably the circulation of mugshots and cross-jurisdictional coordination, and he achieved national fame after foiling a possible plot against Abraham Lincoln in 1861. Yet his Civil War intelligence work for the Union, lauded at the time, was riddled with analytical errors that did more to confuse than clarify. He overcalculated the number of Confederate soldiers, and, while not explicitly stating it, Jeffreys-Jones implies that Pinkerton’s faulty intelligence contributed to Gen. George McClellan’s infamous reluctance to fight.

After spending half of the book writing a biography about Pinkerton himself, the second half of Allan Pinkerton resembles a collection of short stories filled with interesting characters, including one about Jesse James. Jeffreys-Jones describes various cases, but shows a particular interest in the ones about labor relations, ranging from the Molly Maguires to the bloody Homestead Strike. Most damning is the agency’s role in the rigged prosecution of the Haymarket defendants, several of whom were executed following a tainted trial. Jeffreys-Jones acknowledges the ambiguity of innocence in that case but insists the agency’s conduct corrupted the judicial process nevertheless.

Corruption and a growing reputation as a tool of the rich eventually caught up to the Pinkertons, but it didn’t stop them. Even after the 1893 Anti-Pinkerton Act sought to curtail their federal reach, the broader model they created — contract security, unaccountable surveillance, corporate policing — continued to grow. From their involvement in crushing labor uprisings to their quiet influence on federal intelligence structures, Jeffreys-Jones insists that the Pinkertons helped normalize the idea that private interests could legitimately wield coercive power. That legacy extended into the 21st century, influencing everything from the rise of the FBI to the post-9/11 proliferation of private security contractors.

A distaste for “Pinkertonism” from Jeffreys-Jones often oozes off the pages at times. His eagerness to pigeonhole Pinkerton into an ideological category can come across as an inability to grasp the complexities of the human experience. He seems puzzled that the detective and business leader could “uphold liberal principles” such as abolitionism while opposing organized labor. The author concludes Pinkerton must have been faking those ideals for financial gain, even though those two seemingly conflicting convictions would not have appeared especially inconsistent to the many northern industrialists who funded the antislavery movement.

One of the more peculiar refrains in Jeffreys-Jones’s narrative is his insistence on casting Pinkerton as a “protofeminist” on account of his employment of Kate Warne, a pioneering female detective. The relationship, along with Pinkerton’s broader engagement with women in the agency, certainly merited deeper discussion in the book. But the framing feels off. Pinkerton lived in 19th-century America, not the Middle Ages, and female spies had long operated in U.S. intelligence circles. Although Jeffreys-Jones repeatedly invokes Warne’s presence to polish Pinkerton’s feminist credentials, he eventually concedes there were “limits to Pinkerton’s feminist enlightenment.” From there, the analysis veers into pop psychology: Pinkerton, we are told, may have married an orphan so he could “control her,” a theory scarcely supported by the rest of the text. Likewise, his opposition to his daughter’s suitor is cast not as ordinary familial tension but as an ideological failure to adhere to feminism, though, notably, she married the man anyway.

Despite some ideological eccentricities, the subject of the book is so interesting that it overwhelms the staleness of the political outlook that its author tries to inject into it. Allan Pinkerton: America’s Legendary Detective and the Birth of Private Security offers a riveting account of a largely overlooked figure whose shadow still looms over modern law enforcement and private security.

Carl Paulus is a historian from Michigan and author of The Slaveholding Crisis: The Fear of Insurrection and the Coming of the Civil War.