What happens to older and forgotten books? Is there a way to keep them available so that the next generation can have the benefit of them?

Today’s public libraries pride themselves on being up-to-date, from technological resources to book inventory. Many automatically dispose of books that haven’t been checked out in a certain number of years.

A friend of mine recently went to a chain bookstore in search of books she remembered from her own childhood to give as gifts to her grandchildren. She discovered to her surprise that books like that are not readily available. And Diary of a Wimpy Kid doesn’t compare to, say, Robert Louis Stevenson for its model of character development or idealism.

In public schools, textbooks and “free reading” books have given place to iPads with pre-uploaded material that allows a teacher to monitor how many electronic pages have been turned (no way to check whether the pages were comprehended, of course!). Contemporary kid lit — and even worse, YA (young adult) literature — not only butchers what remains of the King’s English, but often features ever-less-desirable models of behavior.

It’s not easy to find plain old good books for elementary- and secondary-age children, books about decent people doing interesting things, using sentences over six words in length and words that broaden the reader’s vocabulary. These are the books that turn a kid into a reader, the kind of book that educator Charlotte Mason would have described as an “inspiring tale, well-told.”

Well-educated people over 50 who grew up reading detective stories and dog stories and horse stories, along with Stevenson and Charles Dickens as summer reading (and maybe Leo Tolstoy in high school), may not realize how unfashionable and how rapidly disappearing those old standbys are. Classical schools and homeschoolers seem to be the only people who want them today.

Meanwhile, there are a lot of us around who have shelves full of good books that we don’t know what to do with. If it causes you grief to hear of boxes of hardbacks and leather-bound classics being thrown into a van at a library loading dock because they’re being taken to the dump and have been on the “for sale” shelf of the library for too long, then maybe you should start your own private library. It doesn’t have to be focused only on kids: there is nothing to stop political junkies or sci-fi fans from starting their own libraries and sharing their collections.

New Solution to Old Problem

Private libraries may be an answer to the problem of how unfashionable but good old books can be made available to those who want and need them. Here, technology is the friend of the old-fashioned: it solves the problem of how to match books with the people who want to read them.

The private library movement is growing around the English-speaking world; close to a hundred are listed at Biblioguides. There’s even a podcast for Christian homeschool private libraries. Sara Masarik, a Hillsdale- and Oxford-educated mom, is a primary influencer in the movement.

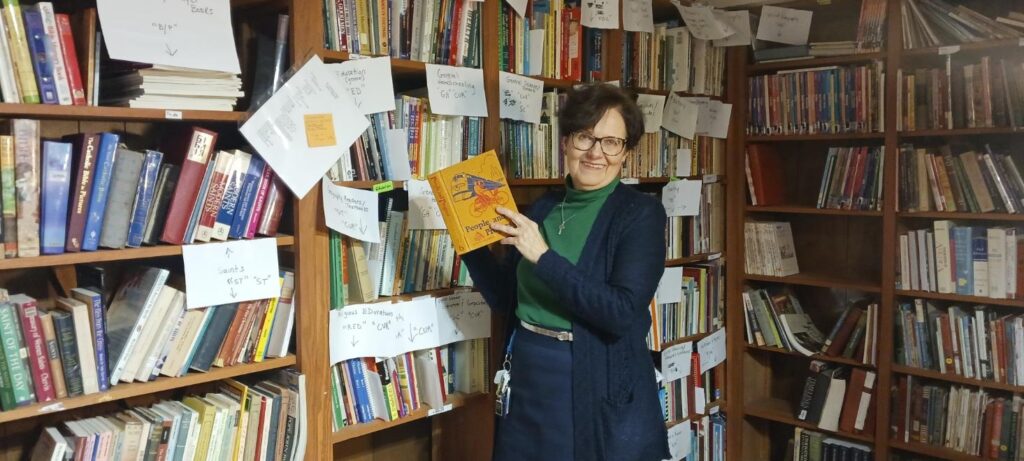

Image CreditStella Morabito

How To Do It

The necessary ingredients to start a private library are few: books, shelves, the right technology, and volunteers. Space is nice, but optional: one private library in Texas is in a converted school bus! The last ingredient is perhaps the most difficult for us conservatives who, after all, tend to pride ourselves on our independence and don’t easily ask for help.

I talked about my idea of a lending library to friends for a couple of years before one mom voluntold her high schooler to come help a couple of afternoons a week.

At first, we entered books into an Excel file. Then someone told me about Library Thing — and it was a new ballgame. Once we had chosen a name, Library Thing let us list every book in a digital catalog. Suddenly random books became Saint Columba’s Place. (St. Columba was the sixth-century Irish monk who went to war over a book. For his penance he left Ireland and founded a monastery on Iona, which later converted the Picts and Scots.)

Library Thing and TinyCat are the right technology. Library Thing is a free digital database, begun by a former classics major to catalog his own books to share with his friends. It now lists more than 150 million books and other media, each an item in someone’s personal or organizational library. TinyCat is the portal to access the database; think of it as the storefront. It syncs with the library’s catalog, and allows members to view the inventory and check out books. A library pays a fee to use TinyCat, which is why private libraries have to charge membership fees.

Entering the first 2,000 books into the digital catalog took a summer of two high school volunteers working several hours a week, even though each book takes only about 30 seconds. Fortunately, at the beginning I had an old clunker of a laptop which I could dedicate to St. Columba; a volunteer later donated a new one, along with a barcode scanner and other equipment.

This segues to the most important ingredient: volunteers. Those high school students were absolutely indispensable — as are the adults who now donate three or six hours a week, contribute supplies, donate books, enter books, and arrange shelves … It could not happen without more than a dozen good workers who share the vision and are willing to put their time where their heart is.

TinyCat proved its value in setting up a circulation system. In olden days there were individual cards glued in the back of books — today there are barcodes. Barcodes purchased from Library Thing arrive at the doorstep ready to be used.

Every book must have a barcode and it must be scanned into TinyCat. The barcode is affixed to a library label, previously attached to the book, and then scanned. This identifies each individual item in the library. All that volunteer effort was needed before we could check out the first book!

The reward is that the check-in process takes literally seconds. Patrons can search our database at home to find books they want, and put them on hold. When they have their appointment, they come in and pick up their books.

Meanwhile, as all this work was going on, policy decisions had to be made: how to arrange books on the shelves (we went with a modified Dewey Decimal system), membership rules, fees, and hours of operation.

Since I live in a residential neighborhood, I had to apply to my local zoning office for an in-home business license, and I had to ensure that the library will not cause traffic problems for the neighbors. Thus, volunteers crowd five cars into my driveway so that library patrons may park on the street for their 15-minute appointments.

It’s a delightful irony that the best that has been thought and said in the past is made available to the future thanks to the technology of the present.

Connie Marshner lives in Front Royal, Virginia, where she houses St. Columba’s Place library in her basement. She is also the author of Monastery and High Cross: The Forgotten Eastern Roots of Irish Christianity.