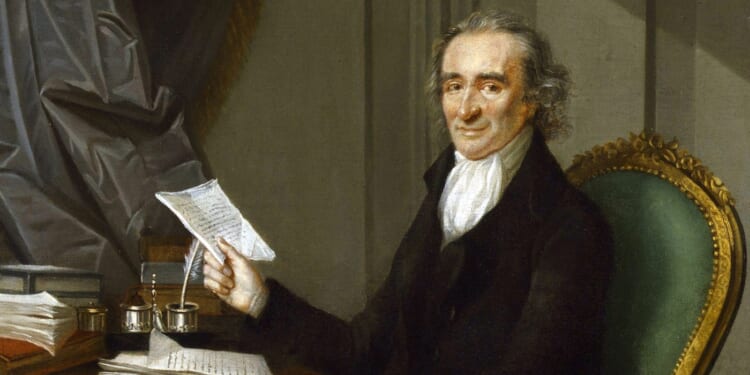

It is arguably the best-selling (non-biblical) work in our nation’s history and inarguably one of the most influential. A treatise that helped lead to the creation of a new nation, it was written by someone who had spent little more than a year on this side of the Atlantic before taking up his pen.

First published a quarter-millennium ago this month, Common Sense launched a continental debate about whether the American colonies should declare their independence from Great Britain. As our nation prepares to celebrate its 250th birthday, a creation that Common Sense helped bring about, it seems appropriate to reexamine Thomas Paine’s seminal work in light of both the American Revolution and events since.

Colonial Sensibilities

In many ways, Common Sense is of its time. For starters, it reflects a much more literate and literary society than our present age. While not particularly lengthy, the work exceeds 15,000 words (more than 20,000 if one counts the introduction and a later appendix). It also contains allusions to British history and long discussions of the merits of various forms of government (e.g., monarchy, republic, etc.).

No matter the topic — tariffs, immigration, you name it — one finds it difficult to imagine that any 46-page document discussing current affairs, as opposed to a TikTok video or podcast, would become a viral hit in our society. Yet Common Sense sold the colonial equivalent of millions of copies in the first half of 1776, demonstrating both the relevance of its content to that historical moment and the way in which colonial society used the printing press to debate and spread Enlightenment ideas.

A work that Paine intended for the masses also reflects the popular sensibilities of that 18th-century society. A lengthy discussion about the ills of monarchy has anti-Catholic rhetoric interspersed within it, culminating in Paine’s assertion, obviously intended as an insult, that “Monarchy in every instance is the Popery of Government.”

Coming after battles against the British Army at Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill the prior year, Paine wrote about how the bloodshed represented a Rubicon crossed: “Can ye give to prostitution its former innocence?” He noted that households outside Massachusetts that had not had homes and property destroyed were in no position to demand a reconciliation with Britain. In even more blunt language, Paine wrote that those who had suffered horrors at the hands of the British, “and still can shake hands with the murderers,” are “unworthy the name of husband, father, friend, or lover, and whatever may be your rank or title in life, you have the heart of a coward, and the spirit of a sycophant.”

American Empire

In some sections, Common Sense seems archaic amid the philosophical discussion of systems of government — a discussion that by modern standards appears consigned to university seminars and Enlightenment-era literature — and righteous indignation at the misdeeds of King George III and the British Army. Yet portions seem eerily prescient and relevant still to our 21st-century society.

While highlighting the brutality of British rule in the decade leading up to the Revolution, Paine also noted the impracticality and absurdity of a small island nation trying to rule an entire continent an ocean away: “It is evident they belong to different systems.” He added words that might serve as music to the ears of some modern audiences: “England to Europe: America to itself.”

Paine viewed what would become the United States as striding above the parochial differences of quarreling European powers. He spent several pages of Common Sense discussing America’s ability to build a navy using its virgin forests and the military and economic advantages that would come from it. Paine believed in free trade and thought America needed to avoid getting dragged into Britain’s disputes with other European powers in ways that would harm American commerce:

Our plan is commerce, and that well attended to, will secure us the peace and friendship of all Europe, because it is the interest of all Europe to have America a free port. … As Europe is our market for trade, we ought to form no political connexion with any part of it. ‘Tis the true interest of America, to steer clear of European contentions, which she never can do, while by her dependence on Britain she is made the make-weight in the scale of British politics.

While the growth of an American continent as a superpower equaling, if not succeeding, the ancien regime in Europe might appear inevitable from 250 years’ distance, it was far from clear on the eve of the Revolution. It speaks to the power of works like Common Sense that its author could articulate a series of circumstances that played out surprisingly accurately over the centuries.

One wonders what Paine, George Washington, and other members of the Revolutionary cadre might think of their handiwork 10 generations or so removed from the nation’s creation. The fact that much of the vision of Paine and other Founding Fathers came to fruition speaks to the determination of succeeding generations to make it a reality.