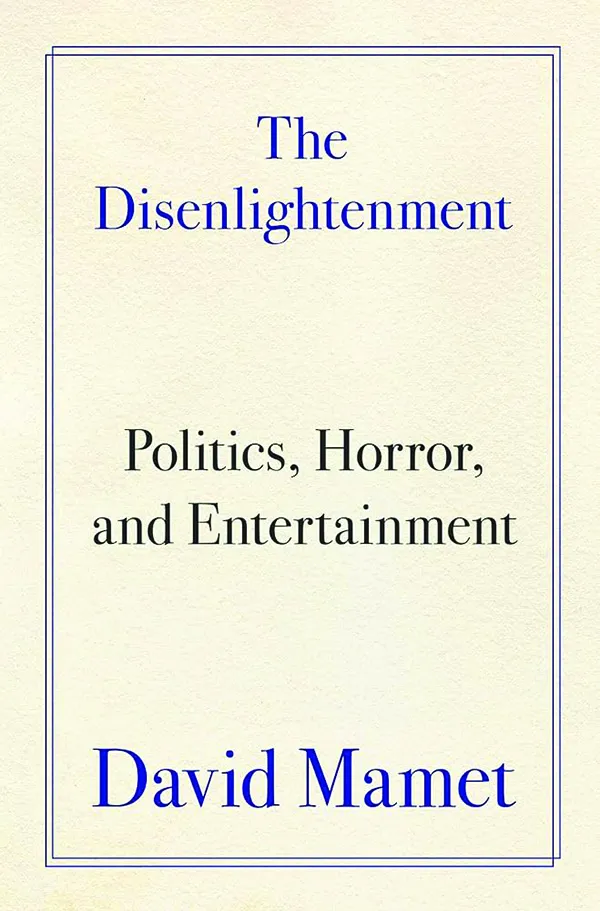

You’ve seen this movie before: a Jewish intellectual who brings not peace, but a sword. This time, however, the sword is swung with abandon. “A Jew who votes for the Democrats,” David Mamet writes in The Disenlightenment: Politics, Horror, and Entertainment, “is a damned fool.” “O.J. Simpson,” he thunders, “killed two people as incontrovertibly as Jack Ruby shot [Lee Harvey] Oswald.” Speaking of the latter: “I’ve been in the editing room for 45 years, and I assure you, the [Zapruder] film is faked.” Mamet’s willingness to let the bodies hit the floor rivals that of Roman Emperor Commodus. He dismisses the critical flower of American poetry as “Largely drivel — Walt Whitman and Robert Frost’s work would not be out of place on greeting cards.” In their place, Mamet prefers the work of Muddy Waters and Bob Dylan.

The latter choice is particularly appropriate because if your last exposure to this author was via his universally cherished Glengarry Glen Ross (1992) or Wag the Dog (1997), this 238-page shotgun-staccato collection of barbaric-yawp ranting will hit you like Messrs. Zimmerman, Kooper, and Bloomfield cranking up at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival. And the hits keep coming, like a rolling stone: “Since [Barack] Obama the deep state … has been the enemy of Constitutional democracy.” “’Intersectionality’ is a word meaning ‘All of us want all of you dead.’” “The brownshirts of Antifa exist to silence not oppression, but reason.” “Trump is a hero, and his heirs will, God willing, increase the longevity of the American Experiment.” Readers with sensitive natures, emotionally or politically, will feel nothing less than pummeled by the time they reach the book’s final three words, which are a defiant “God Bless America.”

Yet to read The Disenlightenment as a mere “politics book,” a fellow-traveler to those innumerable quick-bake ragebait titles enjoying fruit-fly relevance in bookstore windows before finding their natural forever home beneath the crooked leg of a folding card table, would be to miss the point entirely. This is really something quite new: a three-act play in which all three acts occur at the same time.

Because Mamet is a scriptwriter, he doesn’t quite trust the audience to pick up on this without help. So we get multiple references to the three-act format throughout the book, coupled with an essay on the “zero point” that defines a successful play and a winking aside to the ending of The Sixth Sense (1999). For purposes of awakening the reader’s skepticism, which of course is tied tightly to perception, Mamet a few times offers entirely and deliberately contradictory ideas of “what this book is about.” The purpose is to make sure the reader continues to hold that idea, of what the book is about, across all 44 of the short essays that comprise it. It can feel a bit heavy-handed at times, but what good is a joke if most of the audience doesn’t get it at some point?

The first act of The Disenlightenment is fairly simple, being an explicit statement of conservative delight at President Donald Trump’s election, particularly as it regards the preservation of Israel. Stating that “For the last four years, Israel has been the leader of the Free World,” Mamet frames America’s existential crisis as one in which Islam, not Russia or China, is the ultimate enemy. He takes American Jews to task repeatedly for their failure to support Trump, noting that they were the only demographic group that didn’t swing at least somewhat away from the Democratic ticket in 2024. “The horror of October 7, 2023, did not bring Western Jews into that state [of historical awareness] but only further into the service of adversaries who sided with the assassins, and call it liberalism.” He frames the 2024 election as one in which everyone but American Jews came together to protect both America and Israel from totalitarian oblivion.

No stranger to the strategies of good playwrights in general and the best playwright in particular, Mamet leavens this winter-of-our-discontent-esque diatribe with generously ladled examples of painfully quotable wit. He pokes fun at fellow screenwriters who rely on witty dialogue: “We enjoy Greek tragedy, [Henrik] Ibsen, [Friedrich] Schiller, and Moliere in translation.” Regarding critical acclaim, and channeling Samuel Johnson in doing so: “There is no book or film so bad that it is issued without the enthusiastic quotes of some whore or dolt.” As to why writers don’t need to work together: “Thwarted inspiration will search for an outlet, which can be most easily found today in the writing of refrigerator magnets.” Regarding the power of pop culture: “American women, as if on the instant, have all adopted the baby-duck voice.”

We experience the second act as a frequent refrain to the horrors of gender ideology, diversity, equity, and inclusion, and willfully destructive social policies. Dozens upon dozens of times, Mamet expresses disgust and horror at 2023 attitudes regarding transgender and multiple-gender ideology, describing progressives not as fetishists but as fetuses: “The infant lives in a preverbal universe … and if uncorrected must develop into group sociopathy … herd tropisms … their feelings cannot be reasonably be expressed as ideas.” He despises people who refuse to have children due to environmental concerns: “Like [George] Washington and [Thomas] Jefferson’s ‘bequests’ to their slaves, the nulliparous chant means … ‘I leave the earth to you fools.’ See also liberals’ infatuation with those who can’t control themselves … This, understood as sympathy, is actually envy: the various enjoyment of infant license.”

In the middle of the book, we are treated to a lovely and perceptive essay on the “zero point” in theater productions. “[The dramatist’s] great task must be to send them out into the [intermission] lobby second-guessing about the next act but coming to the wrong conclusion.” Having taught the reader something about his art, he immediately returns to willful courting of controversy. Regarding public discussion of alleged Brian Thompson assassin Luigi Mangione’s childhood, Mamet states that “it should not be humanized. One must turn away. The Talmud teaches that one should avert one’s eyes from two animals copulating.”

Which sets us up for the third act, which is sprinkled throughout the book but really only comes together in the reader’s mind near the end. Having reached a literal “zero point” by forthrightly likening an as-yet-unconvicted prisoner and his family history to animal copulation, Mamet reaches back into the sky, quite literally, by noting that there are two places in America above which pilots are permanently restricted from flying: the White House and Disneyland. Rather unsubtly, he suggests that these generically represent the two sources of evil in this country, an ever-grasping bureaucracy and an endlessly greedy media.

“The state is only equipped to raise slaves,” Mamet notes. It is also, as of late, only interested in encouraging a slavish conformity. “These, the Nomenklatura in Soviet Russia … Today they are the proponents of DEI.” He purposely blurs the boundaries of media church and diversity state, with the Disney/D.C. connection alive in the reader’s mind. The ascension of streaming services, which remove the customer’s ability or even desire to select one piece of media over another, creates a sea of slop on TV, defined by the universal qualities of mediocrity and political reliability. “Folks do not willingly choose their entertainment on the basis of the purveyor’s political notions. They will only do so when they have no choice — as with the hegemony of the streaming services.” Going further: “The racial and ‘gender’ politicization of our time does not stifle ambition; it only kills ambition to produce.”

Mamet directs no small amount of animus toward the internet, the omnipresent smartphones, and the dopamine-dispensing apps that encourage their users to continually “check in.” Surely this attitude is no longer controversial in an era where the wealthy increasingly define themselves by disconnection from the electronic leash, but to the baby-duck-voice (and Orwell-duckspeaking) crowd, it might still serve as a novel irritant to provoke a pearl of thought.

MAGAZINE: STRANGER THINGS IS THE HAPPY DAYS OF THE COVID-19 ERA

If there is a false note in this often painfully perceptive book, it has to do with Mamet’s disdain for Top Gun: Maverick (2022). Calling it “the industry’s death rattle,” Mamet seems to be under the impression that it was a green-screen CGI fantasy. It was not; most of the scenes were shot with 10 special cameras installed around and inside a real F/A-18 Super Hornet, while a real aircraft carrier served as the film set for much of the rest. Over 1,000 hours of maintenance went into the Super Hornets during production. As a credentialed pilot, Mamet should have known better, but this is a minor misstep.

And so we have a three-act play of sorts. It begins, not unlike many plays or movies, with joy at a small victory in a long battle before switching into a pessimistic overview of the forces arrayed against the good guys. It then reaches a meta-discussion of the zero point before launching into the final message: our media and our communications require a future revitalization equal to or greater than that of Trump’s recent triumph. If this all sounds familiar, it is because we have seen it on stage and screen many times. Mamet provides no particular plan of corrective action, but surely it is enough, from his perspective, that he has lent his considerable prestige and devoted his considerable effort to a book with little purpose other than to raise the alarm. “It is a crime to shout ‘fire’ in a crowded theater,” he notes. “Unless, of course, the theater is burning, when it is criminal to refrain.”

Jack Baruth was born in Brooklyn, New York, and lives in Ohio. He is a professional-amateur race car driver, a former columnist for Road and Track and Hagerty magazines, and writer of the Avoidable Contact Forever newsletter.