The Venezuelan government published a “state of external commotion” decree on Monday that it has used to crack down on dissent following the United States’s capture of the country’s former dictator Nicolás Maduro.

The decree, signed by Maduro after initial U.S. airstrikes on Caracas but before his seizure, legally grants the authorities extensive powers to arrest supporters of the U.S. attack.

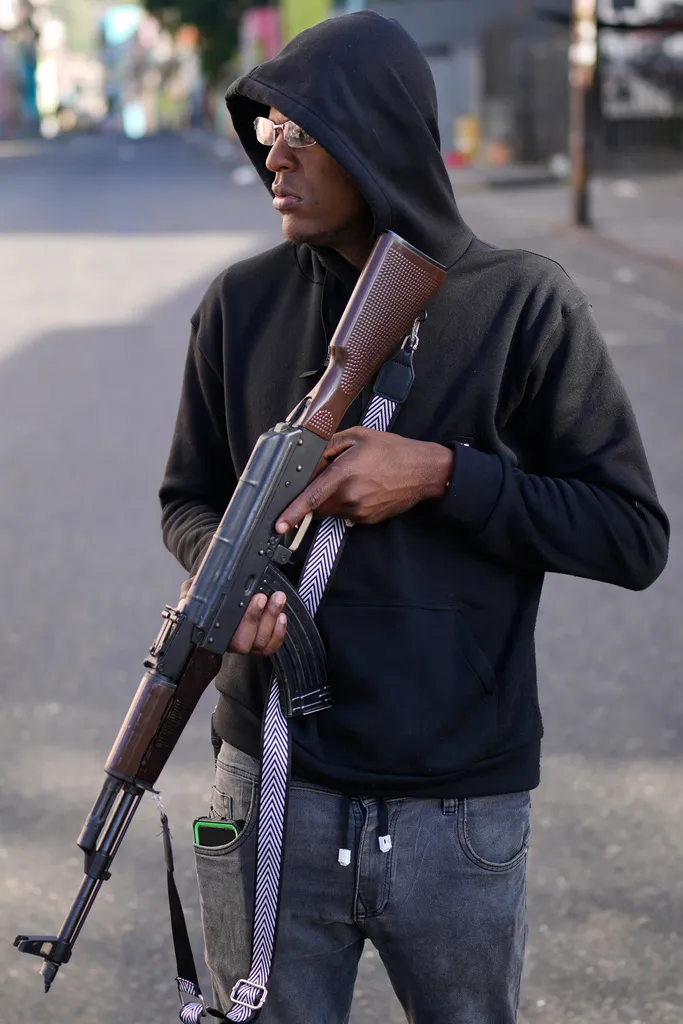

Since the operation, pro-Maduro biker gangs have roamed the streets of the capital looking for opponents of the socialist government. Security forces, including regime-backed militias, have established checkpoints to stop vehicles and search occupants’ phones for evidence of support for Saturday’s strike.

“They went through people’s phones, opening their WhatsApp and typing in keywords like ‘invasion’ or ‘Maduro’ or ‘Trump’ in the chats to see if they were celebrating Maduro’s arrest,” Gabriela Buada, director of Human Kaleidoscope, told the New York Times.

International pro-democracy groups and several countries, including the United States, say that Maduro and his supporters rigged the 2024 election in which the regime claimed victory. The opposition published vote tallies showing that they had won by over 40 points against Maduro.

Despite these signs of the regime’s unpopularity, there have been no public celebrations supporting the overthrow of Maduro. Reports state that many Venezuelans fear being arrested after the government crackdown.

Press freedom in Venezuela is also heavily suppressed. According to the country’s National Union of Press Workers, 23 journalists and press workers have been detained by the Venezuelan government. In total, 180 union members and workers are held by the regime.

However, recent repression is not unprecedented in Venezuela. The authoritarian regime has a long track record of human rights abuses dating back to the presidency of Hugo Chávez. Recently, the government has used U.S. pressure as an excuse to suppress dissent even before the United States’s capture of Maduro.

The National Assembly passed legislation in December ordering up to 20 years of imprisonment for anyone who “promotes, instigates, requests, invokes, favors, facilitates, supports, finances or participates” in the U.S. seizure of oil tankers trading with Venezuela.

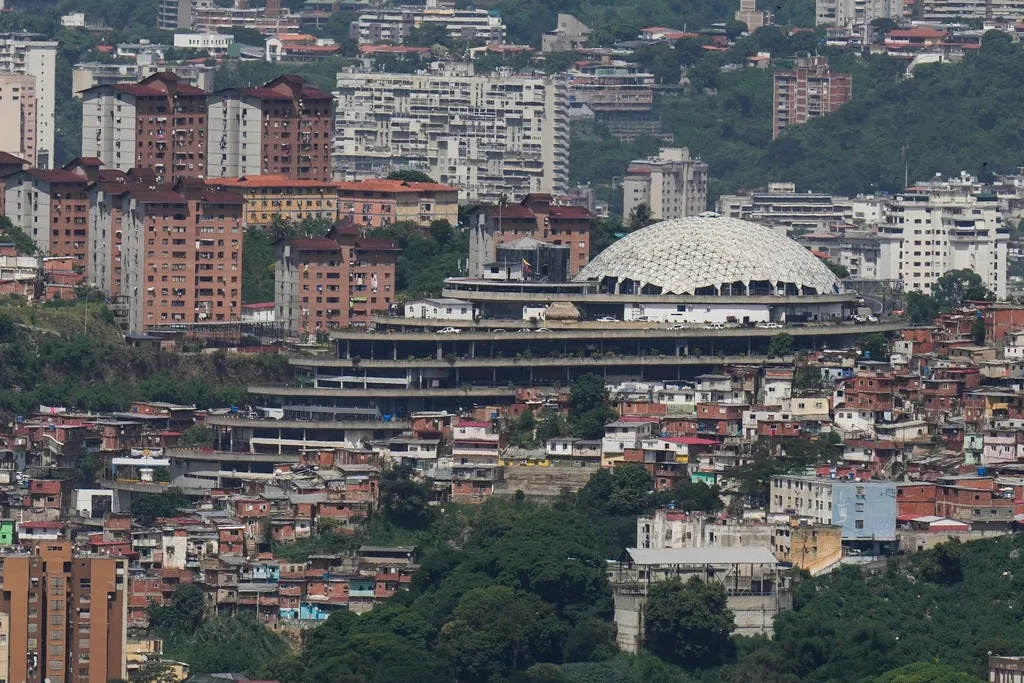

In the same month, opposition lawmaker Alfredo Díaz died while detained at the notorious El Helicoide prison in Caracas. The prison is the headquarters of the SEBIN, the Venezuelan intelligence service, and is used to hold political prisoners.

THE MAIN PLAYERS IN VENEZUELA’S GOVERNMENT AND WHO COULD BE TARGETED NEXT

Almost 900 political prisoners, including 86 foreign nationals, are held by the Venezuelan government. Human rights groups claim they are victims of arbitrary detention and have no communication with the outside world. Ninety are estimated to have serious medical conditions with inadequate treatment, according to Justicia, Encuentro y Perdón.

But things may be slowly changing in Venezuela. President Donald Trump referred to the Helicoide prison on Tuesday, saying Venezuelan interim President Delcy Rodriguez ordered the “torture chamber in the middle of Caracas” to be closed.