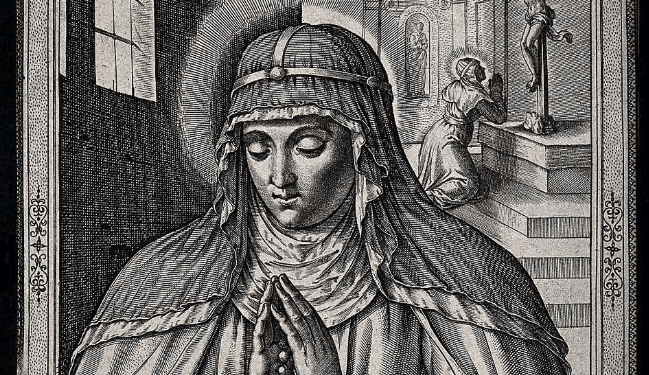

Artists have been depicting the birth of Christ for centuries, but no one made the image warmer and more emotionally accessible than Saint Bridget of Sweden (1303-1373).

It’s a wonderful story: the beloved wife and mother of eight becomes a nun, then a saint, and forever transforms the visual iconography of Christmas. Canonized in 1391, Saint Bridget’s mystical visions of the Virgin and the Nativity had an enormous influence on medieval and Renaissance artists portraying the Holy Family. The impact of these visions can be seen in the work of artists of the current day.

Saint Bridget was born into a wealthy and well-connected Swedish family. Her mother died when she was 11. Two years later, her father arranged for her to be married to Ulf Gudmarsson, a young man of 18 who also came from a well-off and well-connected family. Together, they produced eight children. One daughter eventually became a saint as well, Catherine of Sweden, or Katarina of Vadstena.

In addition to her family, Bridget’s attentions were focused on the needy and less fortunate. She practiced works of charity, aiding the sick and helping girls who found themselves in less-than-honorable circumstances.

After her husband died in (1344/6), religious work became Bridget’s primary focus. As instructed in one of her visions, she founded the Order of the Most Holy Savior, also known as the Bridgettines, in 1344.

Bridget’s many visions were captured in a volume entitled Revelations or Liber celestis revelacionum (heavenly book of revelations) published originally in Latin in the late 1300s. The Library of Congress site describes the work as … “one of the most important and influential works of Swedish medieval literature.”

Bridget experienced several visions as a child, but the most influential occurred in her late sixties. Journeying to Bethlehem to visit the birthplace of Christ, at the Grotto of the Nativity, she experienced a vision centering on the birth of Jesus. It was this revelation that had a profound effect on how artists portrayed the Nativity.

As the recent exhibition at the British Library, Medieval Women: In Their Own Words, (October 2024 to March 2025), describes it, Bridget’s Revelations decisively shaped “the way people pictured Christmas.”

The exhibition described how images of the Nativity changed due to Bridget’s vision:

“The standard image of the Nativity in Western Europe until the 14th century showed the Virgin Mary reclining in bed, as was normal for medieval mothers. Jesus is usually lying in the manger, being adored by an ox and ass… In the 14th century, however, a new type of Nativity scene began to appear, due in large part to Birgitta’s vision.”

Three aspects of her visions became motifs incorporated into the way artists represented the Nativity scene. The first involves the pose or positioning of the Virgin Mary. Before Bridget’s vision, Mary was depicted reclining or lying down after giving birth, as was the Christ child. Bridget’s version presented the Virgin kneeling with her hands clasped in prayer after the birth.

In her vision, as recorded in Revelations, Bridget notes, “When the Virgin perceived that she had been delivered, she immediately bowed her head, and joining her hands, adored her Son with great respect and reverence, saying: Welcome my God, and my Lord, and my Son.”

One example of this is “The Mystical Nativity or Adoration in the Forest,” painted by Fra Filippo Lippi in 1459. Originally designed as the altarpiece for the Magi Chapel in the new Palazzo Medici in Florence.

Annalena Nativity of Jesus Christ by Filippo Lippi

The second distinguishing characteristic was the warm, glowing light enveloping the newborn Christ. In Revelations, she writes, “… then and there, in a moment and the twinkling of an eye, she gave birth to a Son from whom there went out such great and ineffable light and splendor that the sun could not be compared to it.”

The third element of Bridget’s vision presents the Virgin gathering the Christ child up in her maternal embrace. When the Christ child starts to cry and reaches out for his mother, Bridget saw in her vision: “Then His mother took Him to her heart, and with her cheek and breast warmed Him with great joy, and a mother’s tender compassion.”

“The Nativity, The Holy Night,” or “The Adoration of the Shepherds,” by Antonio da Correggio. c. 1529–1530, is a good example of the warm, glowing light, as well as the third element of Bridget’s vision, which became incorporated in many Nativity scenes. This element demonstrates the moment when, looking to comfort her newborn son, the Virgin cradles him in her arms. Instead of leaving him alone in the manger, the Virgin envelops him in maternal love.

When the Christ child starts to cry and reaches out for his mother, Bridget saw in her vision: “Then His mother took Him to her heart, and with her cheek and breast warmed Him with great joy, and a mother’s tender compassion.”

Saint Bridget’s more emotional and maternal vision of the Nativity quickly caught on among artists and manuscript illuminators. It became standard to show the Virgin kneeling with clasped hands, the Virgin and Christ child bathed in warm, glowing light, and the Virgin cradling Christ in her arms, from the late Middle Ages through the Renaissance, and up to the current day.

For example, Saint Bridget’s influence is apparent in the work of contemporary African-American artist Romare Bearden (1911 – 1988). Well known for his scenes of everyday African-American life, his painting “The Manger” includes elements of the Swedish saint’s vision in his portrayal of the Nativity. Mary is kneeling and bending forward and protect the infant Christ child, her hands clasped together in prayer.

Despite the work’s innovative form, we feel an almost primal sense of maternal warmth from the mother figure. Her bent-over stance and oversized hands invoke the act of protection. That an artist like Bearden, whose approach combined modern elements of improvisation, intuition, and avant-garde techniques of Cubism, included elements of Saint Bridget’s vision in his 1945 work, is a testament to the longevity of her impact.

The three elements of Saint Briget’s vision: the Virgin kneeling with hands clasped in prayer, the Virgin and Christ child being bathed in warm light, and Mary cradling Christ in her arms, are active as opposed to passive stances. They provide plotlines, but also serve to engage the artwork’s viewer, summoning emotions, fostering questions, and engaging the senses.

They can even provide a foundation for a sense of Christian community or belonging through the well-known story of the birth of Christ. In addition to their literary value, the visions of Saint Bridget have had a profound effect on artists portraying the Nativity.

Beginning in the Late Middle Ages, the visions of Bridget of Sweden: mother, nun, and saint, provided artists with greater opportunities for making the classic story of Christ’s birth more emotionally accessible, as well as more warmly maternal.

Beth Herman is an artist, essayist, and school docent at The National Gallery of Art. In addition to The Federalist, her essays have been published in The Wall Street Journal, Legal Times, The Washington Times, and on NPR. When not at her writing desk, Beth can be found running or walking with her husband, the author and historian Arthur Herman.