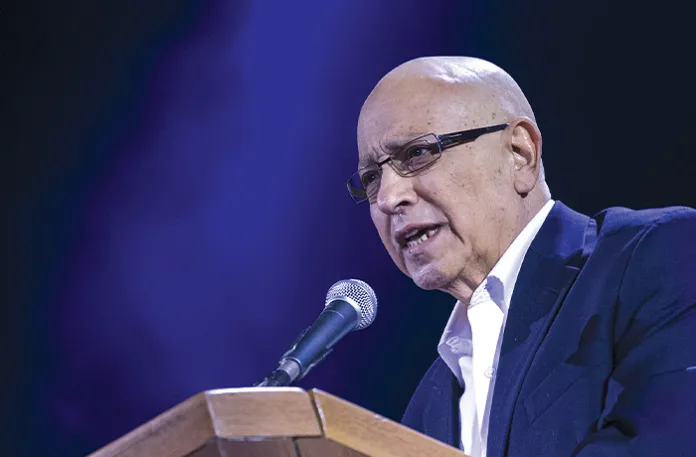

Meir Dagan died in 2016, six years after his tenure as director of the Mossad, Israel’s vaunted intelligence agency, ended. But some of the fruits of his efforts were apparent this past summer, during the so-called Iran-Israel war, when the latter country carried out a series of daring and ultimately successful operations against the Iranian regime. Among other feats, Israel built drone bases inside Iran itself and carried out what is probably the largest decapitation strike in modern military history, eliminating the vast majority of Tehran’s military leadership in one fell swoop. President John F. Kennedy famously said that “victory has a thousand fathers, but defeat is an orphan.” The success of the Iran-Israel war has many fathers, but surely Dagan can be counted among them.

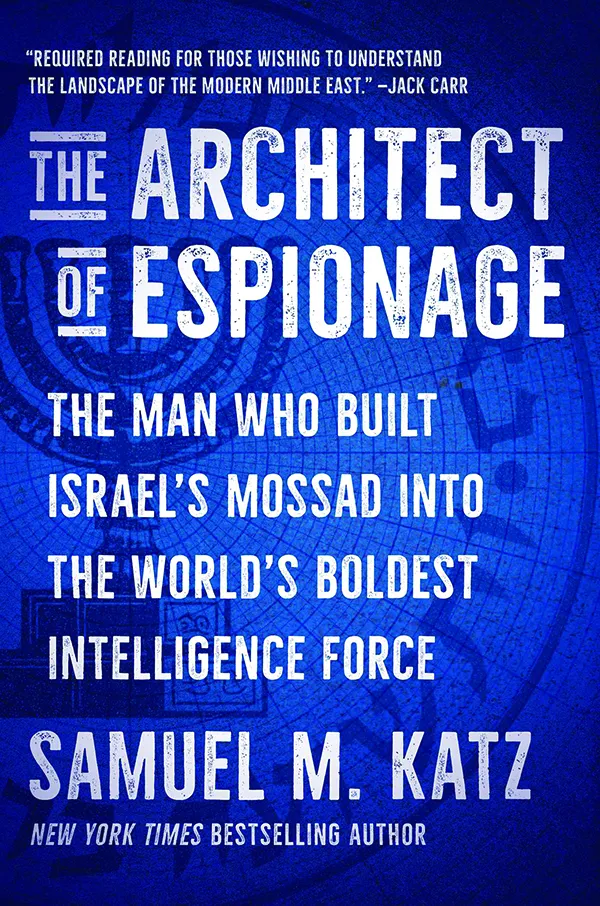

Samuel Katz’s recently published The Architect of Espionage: The Man Who Built Israel’s Mossad Into the World’s Boldest Intelligence Force makes the case that Dagan transformed the Jewish state’s foreign intelligence service, equipping it for its present-day heroics. Dagan was not a natural choice to lead the Mossad, but he was perhaps its most consequential director. Born in Kherson, Ukraine, in 1945 in trying circumstances, his early years were inseparable from the ravages of war and the suffering of the Holocaust. His parents, Shmuel and Mina, were Polish Jews who spent most of World War II in a Soviet work camp. Nazi forces had burned most of their tiny village to the ground. The Soviet “liberators” encouraged the Jews of the town to flee and join them in the Ural Mountains as workers. Schmuel and Mina chose to do so, but most of Dagan’s family did not. Those who stayed, including no fewer than 300 members of Dagan’s extended family, perished.

Dagan’s grandfather had stayed, “convinced that the Germans were too sophisticated and too cultured to wish the Jews of Europe harm.” He was later mocked and then beaten to death by SS forces inside a ghetto, the moment captured on camera by a Nazi photographer. Later in life, Dagan would keep the photo at his desk as a reminder of the dangers of both antisemitism and complacency. The lesson? Wishful thinking was costly. Jews couldn’t afford to be optimistic.

When Dagan’s mother found out that she was pregnant, she had initially thought “that her swollen stomach was the result of malnutrition,” Katz notes. At war’s end, the family briefly returned to Poland, now under communist rule, before making their way to British-ruled Mandate for Palestine. When Dagan was three, the Jewish nation of Israel was recreated from the Mandate, prompting another war and another attempt to murder Jews en masse. But this effort, led by no fewer than half a dozen Arab armies and militias, failed. This time, the Jews of the Yishuv, pre-state Israel, were armed and without illusion. Still, it was a near-fought thing; 1% of Israel’s population were casualties.

More wars followed. And as the fledgling Jewish state grew, the young Dagan grew with it. As a young boy, Meir grew up in awe of the Palmach, the elite commandos who made their mark during Israel’s War of Independence. In 1963, Dagan was conscripted into the Israel Defense Forces. He was prone to breaking the rules from the beginning, sneaking personal weapons into the induction base. Dagan was initially interested in joining Sayeret Mat’kal, the elite Israeli unit modeled after the British Special Air Service. But it was not to be. Instead, he became a paratrooper, experiencing combat before he was 21. He served as a commando on the front lines of the emerging terrorist war in the territories that Israel seized during the 1967 Six-Day War, sustaining a serious injury from a landmine in the process. Dagan had the men under his command dress as Gazans to gather intelligence and patrol beaches while sitting atop camels to pose as Bedouin tribesmen. He created a network of informants whose information would pay dividends. In the era when Israel was still facing threats from Arab nationalists in Egypt and Syria, Dagan was pioneering tactics that would come to define Israel’s wars of the future. In the early 1980s, Dagan ran special forces and intelligence operations in Lebanon, first confronting the threat that would come to define his career: the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Meir loved art and had a “natural ability to draw, paint, and mold creations from clay, stone, and metal.” He spent hours with watercolors or oils. Even in his 20s, he smoked a pipe “like a learned professor.” As one of his compatriots remembered, “He was determined to be unique and he wanted to stand out.” Later, Dagan would become identified with the pipe, a cane, and a love for classical music. Dagan was a vegetarian. “Being eccentric,” Katz notes, “was Meir’s way of letting the army know he would not be overlooked.” It worked.

Dagan’s reputation for unconventional thinking and his personal bravery caught the attention of Ariel Sharon. Years later, when Sharon was prime minister, he appointed Dagan head of the Mossad, Israel’s foreign intelligence service. Sharon believed that intelligence agencies must reinvent themselves periodically. He believed that Dagan, a general with trigger time and contempt for the system, would bring change. “The challenge Dagan faced,” Katz writes, “was reinventing it into a bold fighting force — one built in his image that could meet the threats Israel faced in the post-911 world.”

BOOK REVIEW: YOU SAY YOU WANT A REVOLUTION

Dagan became head of the Mossad during the Second Intifada, in which more than a thousand Israelis were murdered or maimed during a five-year-long terrorist campaign. In the preceding years, the Mossad had botched a high-profile assassination attempt of Khaled Meshal, a top Hamas apparatchik. The agency, some thought, was not up to the immense task confronting it. As an outsider, Dagan was well-positioned to enact necessary reforms.

Yet Dagan’s legacy is inseparable from Iran. The Islamic Republic called for Israel’s destruction and was sponsoring terrorist groups and working on a nuclear weapons program to achieve that end. Dagan stood up a targeted assassination program and built assets inside Iranian borders. But ever the dissident, Dagan became a critic of the country’s approach after he left office in 2010. He was publicly skeptical that an attack on Iran would work. It is an irony of Israeli history that one of the men most responsible for positioning Israel to succeed in the Iran-Israel war may have opposed that very operation had he not died from liver cancer in 2016. Upon his death, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu remarked, “A great warrior has died.” That warrior, and his battles, both on the battlefield and off, are chronicled in Katz’s well-written and engrossing book.

Sean Durns is a Senior Research Analyst for CAMERA, the 65,000-member, Boston-based Committee for Accuracy in Middle East Reporting and Analysis.