Thanks to several decades of comic book saturation at the movies, we all know the plot beats of a superhero epic. An intriguing origin. A rise to power. An unexpected fall followed by a journey in the wilderness. Finally, a heroic victory and return, coming back stronger and wiser than before.

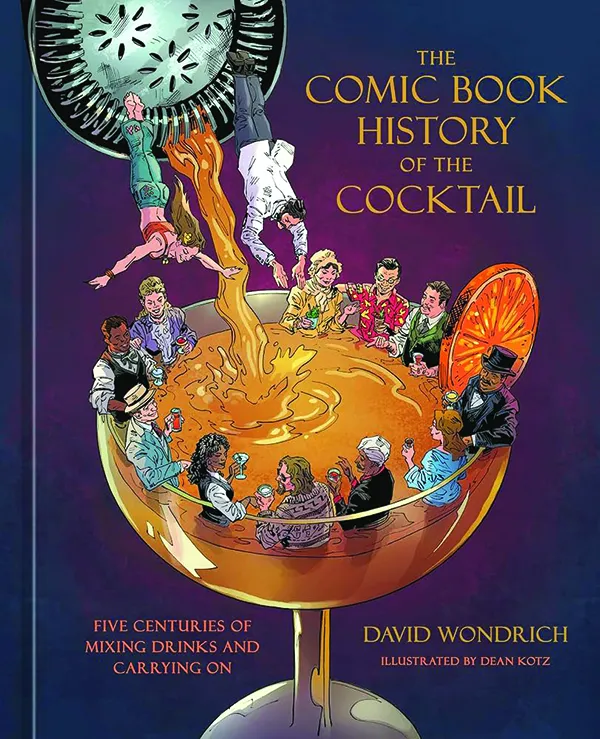

It’s not too much of a stretch to apply that story arc to the cocktail, the subject of the latest book from drink historian David Wondrich. In The Comic Book History of the Cocktail: Five Centuries of Mixing Drinks and Carrying On, Wondrich teams up with illustrator Dean Kotz to tell the story of the mixed drink, from the hazy origins of the first punches to the dark days of Prohibition and disco-era Harvey Wallbangers, to the contemporary revival of old-school drinks, forgotten ingredients, and culinary prestige in the bar world.

For a reader who knows the name Jerry Thomas, what goes into a brandy crusta, or how to make oleosaccharum, much of this is familiar territory from Wondrich’s past forays into drink history, Imbibe! and Punch: The Delights (and Dangers) of the Flowing Bowl. For those less immersed in mixological arcana, you’d be hard-pressed to find a better introduction than this distillation of the major points.

Despite the comic format, the volume’s oversized pages are plenty dense with text. The story begins with murky cocktail pre-history, the spread of early communal punches from Asia and India to England and its colonies in the 16th century, popularizing the combination of spirits, sugar, citrus, and spices. The individualized mixed drink begins to take shape with the American julep, where mint stood in for often unobtainable citrus, and ice, a luxury unavailable to punch-swilling colonizers in the tropics, made its way into cups. By the dawn of the 19th century, bitters combined with spirits and sugar to create the drink we now order as an old-fashioned, simply known at the beginning as a “cocktail.” But the story of that etymology, involving ginger root, horsetraders, and an unexpected orifice, is best left for the book.

There begins mixology’s version of the Cambrian explosion, with diverse and exotic liquors such as orange curaçao and absinthe coming to adorn the cocktail’s simple formula. When vermouth arrives on the scene, making possible the Manhattan, martini, and similar variations, the evolution of the cocktail more or less takes modern shape, becoming a distinctly American cultural export as it spreads around the world, from rum cocktails in pre-Revolution Cuba to its aperitivo adaptations in post-World War II Italy.

Progress wasn’t quite so linear in the United States, of course, with the consecutive blows of Prohibition and WWII hammering bar culture. Wondrich punctures the myth that Prohibition spurred creativity in mixing by inspiring bartenders to mask the taste of bad booze. In reality, imbibers simply took what they could get, and the era’s contributions to the cocktail canon are mostly forgettable. Moreover, talented bar professionals decamped to places where they could ply their trade legally or left the profession altogether. The result was a generational forgetting of hard-won knowledge of the cocktail, a hangover that would last for decades.

A few good things did arise from the eras preceding the contemporary cocktail renaissance, including the tiki bar and assorted tropical cocktails. There was more integration, too, welcoming more women to both sides of the bar and putting African American bartenders on more equal footing. There’s less praise to be lavished on the drinks of the time, which tended toward the simple and very sweet.

The best that can be said for that era is that it incubated latent demand for a well-made drink. By the dawn of the 21st century, a few visionary bartenders were ready to oblige. Led by a handful of pathbreaking bars and a coterie of cocktail lovers connected by the worldwide web, the cocktail made its comeback. Out were sour mix, unmeasured free pours, and two-ingredient drinks; in were hand-squeezed citrus, precision to the teaspoon, and more elaborate recipes. The results are evident to anyone who’s walked into a bar in the past decade. No longer a niche subculture, you can now find solid renditions of the Negroni, old-fashioned, or daiquiri in any decent bar. Search a little harder, and you’ll find mixologists preparing even more baroque concoctions and experimenting with the tools and techniques of molecular gastronomy.

Kotz’s illustrations enjoyably accentuate this history with period-inspired garb and the occasional sound effect; there’s no “Boom! Pow!” of the superhero comics, but he does give us a “shoosha shoosha shoosha” for shaking an egg cocktail without ice and a “shakka shakka shakka” after the ice is added. Chapters also close with recipes for relevant drinks, explained not in dry text but as demonstrations from a couple of fictional bartender characters, more akin to watching a YouTube video than reading a recipe book.

Recipes are not the main point, but Wondrich includes some worthwhile deep cuts, highlighting underrated rarities rather than repeating the classics everybody knows. One of my personal favorites, the genever-based improved Holland gin cocktail, is among them. I also found a few new-to-me drinks I’ll be adding to my repertoire, such as the vintage Cuban Benjamin Menéndez special (Scotch, sugar, lime, and mint) and the Wondrich-original Giacomo Joyce (Irish whiskey, blanc vermouth, coffee liqueur, and Peychaud’s bitters). Honestly, that’s more than I can say for many contemporary cocktail books whose recipes skew so preparation-heavy that I never actually make them.

REVIEW: THE UPSTANDING CAMERON CROWE

Curiously, this book comes out at a time when the bar industry is in a second period of forgetting, not nearly as severe as the one caused by Prohibition, but nonetheless significant. Bartenders who came up during the 21st-century renaissance are aging out of the profession, an exit often hastened by the COVID-19 pandemic. The new generation has come into a cocktail scene that’s no longer a scrappy underdog, but one able to take for granted a vast array of tools, techniques, and ingredients that were rarely seen just a decade or two before. A cocktail invented today may look better on Instagram than it tastes in a glass. As Wondrich laments in an ambivalent parting note, “The emphasis in recent years on mixing drinks as a modern art, rather than as a traditional craft, and on creation over execution, sometimes makes for sketchy foundations.”

Still, we’re fortunate to be living in a golden age of cocktails, even if today’s bartenders are less enamored of the vintage drinks that excited those who ushered in the cocktail renaissance. And if Wondrich’s illustrated history inspires more of them to get back in touch with the roots of the craft, that will be an accomplishment worth toasting.

Jacob Grier is the author of several books, including The Rediscovery of Tobacco: Smoking, Vaping, and the Creative Destruction of the Cigarette, The New Prohibition: The Dangerous Politics of Tobacco Control, and Raising the Bar: A Bottle-by-Bottle Guide to Mixing Masterful Cocktails at Home.